Stories Behind the Stones

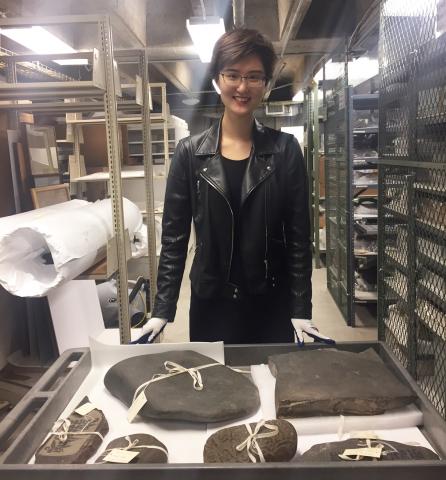

Priscilla (Qizhen) Zhang ’19, LYNK Curatorial Intern

As an Architectural Studies major and Religion minor, I am interested in religious art. Not only because of its often majestic and beautiful characteristics, but also because there are always religious stories behind the art, which makes the objects more mysterious and attractive to me.

When the Museum moved from the Dwight Memorial Art Gallery to its current site in 1970, many things were packed in boxes for transport. One of the boxes contained objects that originated in Tibet. The eight prayer stones from this collection caught my eye as I examined them with Associate Curator of Visual and Material Culture Aaron Miller. The carvings on the stones clearly carry a great deal of meaning. Intrigued, I decided to research these prayer stones. By doing this, I was able to learn more about the objects themselves and the stories behind them.

Before introducing my discoveries about these stones, I would like to define several important concepts in Buddhism that are critical to a discussion of these objects.

Dharma is a key concept in Buddhism, referring to the teachings of the Buddha, or cosmic law or order

Lama is a title for a Buddhist teacher in Tibetan Buddhism

Merit, is a concept that lies in Buddhist ethics. It can bring good results and contribute to one’s growth towards enlightenment. Making and accumulating merit is one of the most important things in the practice of Buddhism.

These prayer stones are actually known as “Mani Stones,” because most of them are inscribed with the scripture “Om mani padme hum,” which is the mantra of Avalokiteshvara, the Buddha of compassion. In terms of the spiritual context of the art of stone, Tibetans believe inscribing Buddhist images or sacred Mantras on rock or on any other hard surface will provide enduring merit and positive energy for the artists. Inscriptions on stones are considered durable and long lasting. We can also see this practice in churches, temples and epitaphs all over the world.

—

Maker Unknown (Tibetan or Indian), Mani stone depicting Shakyamuni Buddha, 19th century or earlier, stone, 3 1/2 in x 13 1/2 in x 18 1/4 in. Gift of Marcus Carleton, in memory of his mother, Celestia Carleton (Class of 1854), 1903.2.J.OII.

I have picked three of the stones which have carved images and would like to tell the stories behind them.

1 Mani stone depicting Shakyamuni Buddha

Different Buddhist figures have different mudra. A mudra is a symbolic or ritual gesture in Buddhism. We can identify many Buddhist figures by their mudras. On this stone, for instance, the right hand mudra of the Buddha is known as Bhumisparsa mudra or “earth touching” mudra. It is a common mudra for Gautama Buddha, who is also known as Shakyamuni Buddha. Just before Gautama attained enlightenment, the demon king Mara tried to frighten him with armies of monsters and pull him from his meditation under the Bodhi tree. However, Gautama did not move. Then, Mara claimed that he had gained enlightenment himself and his armies declared that they were his witnesses. Mara challenged Gautama by asking him who would speak for him as a witness. Then Gautama reached out his right hand and touched the earth. The earth itself roared, “I bear you witness!” and Mara disappeared. Later, Gautama attained enlightenment and became a Buddha.

Maker Unknown (Tibetan or Indian), Mani stone depicting Milarepa, 19th century or earlier, stone, 1 5/8 in x 17 1/4 in x 18 in. Gift of Miss Jessie R. Carleton, in memory of her mother, Celestia Bradford Carleton (Class of 1854), 1910.7.J.OII

2 Mani stone depicting Milarepa

The incised Buddhist figure on this stone is Milarepa, considered one of Tibet’s most famous yogis and poets. His original name was Mila Thopaga, meaning “delightful to hear.” Thus, his representative posture is to raise his right hand to his ear. He also liked singing and composing songs. In many of his songs and poems he taught the path to Buddhahood. The story of Milarepa is one of Tibet’s most beloved stories. Thopaga’s family was wealthy and aristocratic. However, after his father died, his uncle and aunt divided the property and took his father’s place. Milarepa began to learn sorcery under his mother’s encouragement, but he soon realized that his black magic harmed innocent people. He was brought to a Dharma teacher to learn a new path.

Milarepa’s teacher tasked him with a long period of manual labor—a common practice in Buddhism— intended to make Milarepa stop clinging to himself and place his trust in his teacher. The teacher’s harsh methods allowed Milarepa to overcome the evil karma he had created and prepared him for his education. To practice what he was being taught, Milarepa lived in a cave and devoted himself to Dharma. When he was meditating, he only wore a white cotton robe, even in winter, which earned him the name by which he is known: “Mila” means “great man,” and “repa” means “the cotton-clad.” The belt across his chest is called a meditation belt; it is another important clue to identifying the image on the stone.

Maker Unknown (Tibetan or Indian), Mani stone dedicated to Rinchen Gyatso, 19th century or earlier, stone, 3 in x 13 1/2 in x 16 1/4 in. Gift of Marcus Carleton, in memory of his mother, Celestia Carleton (Class of 1854), 1903.1.J.OII

3 Mani stone dedicated to Rinchen Gyatso

The main purpose of inscribing mantras on stone is not only to accumulate merits and earn virtue for oneself, but also to wish for the longevity of one’s master. Students often carve images of their masters along with inscriptions. This stone is a perfect example. The mudra of this figure is called a teaching mudra, therefore the figure might be a learned Tibetan monk or teacher. If we look at the stone carefully, we see that there is an inscription below. It reads “Kyab Ney Lama Rinchen Gyasto la Namo,” which means “(I) prostrate to (my) Lama Rinchen Gyasto.” From this, we learn that the image above depicts Lama Rinchen Gyasto and this stone was probably carved by one of his students.

—

The carving of Mani stones is an important folkway in Tibet and places where Tibetan culture permeates. It is a method for recording people’s hope and respect and holding them for hundreds of years. In this sincerely religious region, Mani stones are placed near rivers, creeks and on high mountains, and at the entrance gates of monasteries and villages. Hundreds or thousands of them have also been placed together to construct Mani walls. In much of Tibet, you don’t see skyscrapers or crowds of people or the hustle and bustle of the big cities. You see nature with pure color, one or two people with animals, and endless Mani walls. When a visitor to the region brings back a Mani stone, he or she also brings back peace.

The eight Mani stones in the MHCAM collection likely date from the nineteenth century (or earlier) and are from Museum donations in 1903 and 1910. As a 2018 LYNK summer intern, I was able to research these objects and bring this collection into the light, recovering the stories carried by these mysterious objects.

GIVE

GIVE