When creative writing professor Sam Ace wanted to bring students in his course, “Poetry and Image: Formations of Identity,” to the Museum, we were excited to brainstorm new ways of thinking about text and image. In planning our session together, the Museum’s newly-installed Barton Lidice Benes work immediately came to mind as a perfect focal point for the visit.

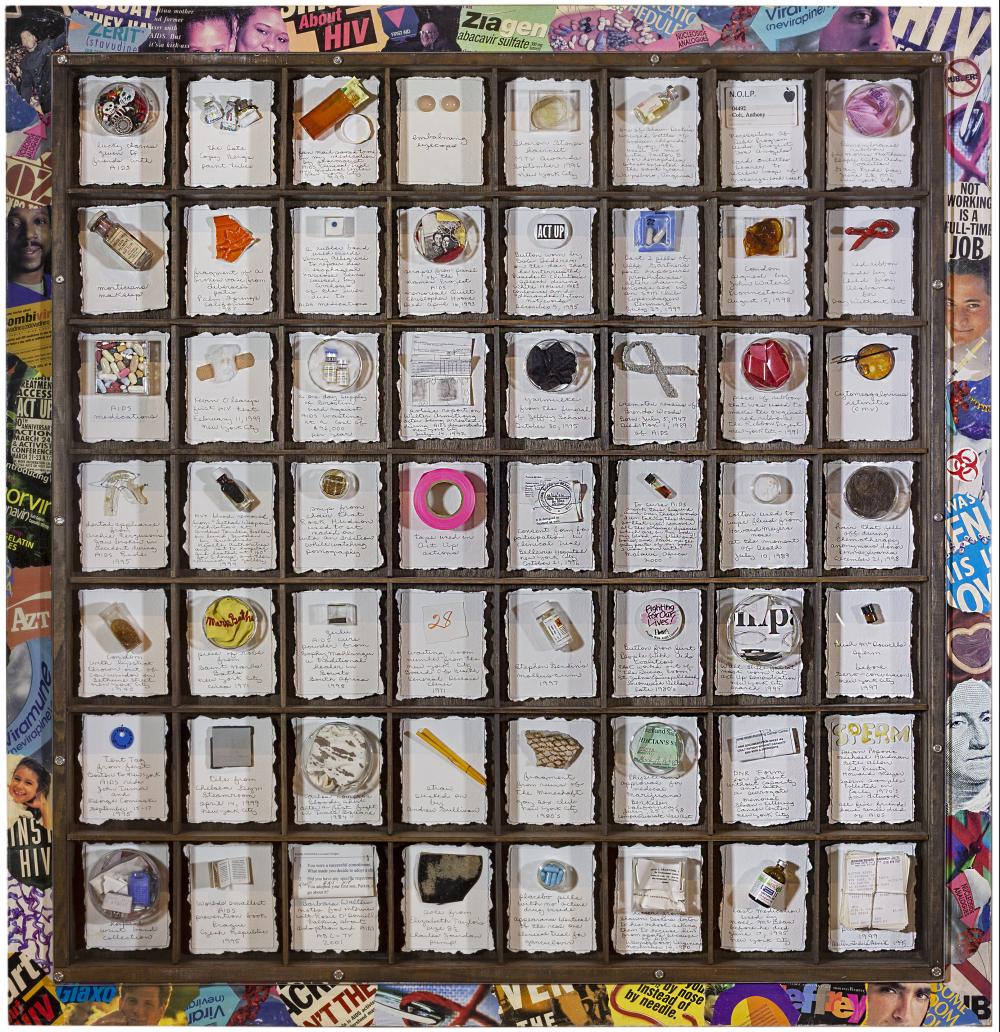

Barton Lidice Benes (American, 1942–2012) was a prolific artist who created assemblages of found, donated, and collected objects. He used the everyday mementos of childhood in his early work, and later made sculptures and shadow boxes from everyday objects as well as paper and other materials.

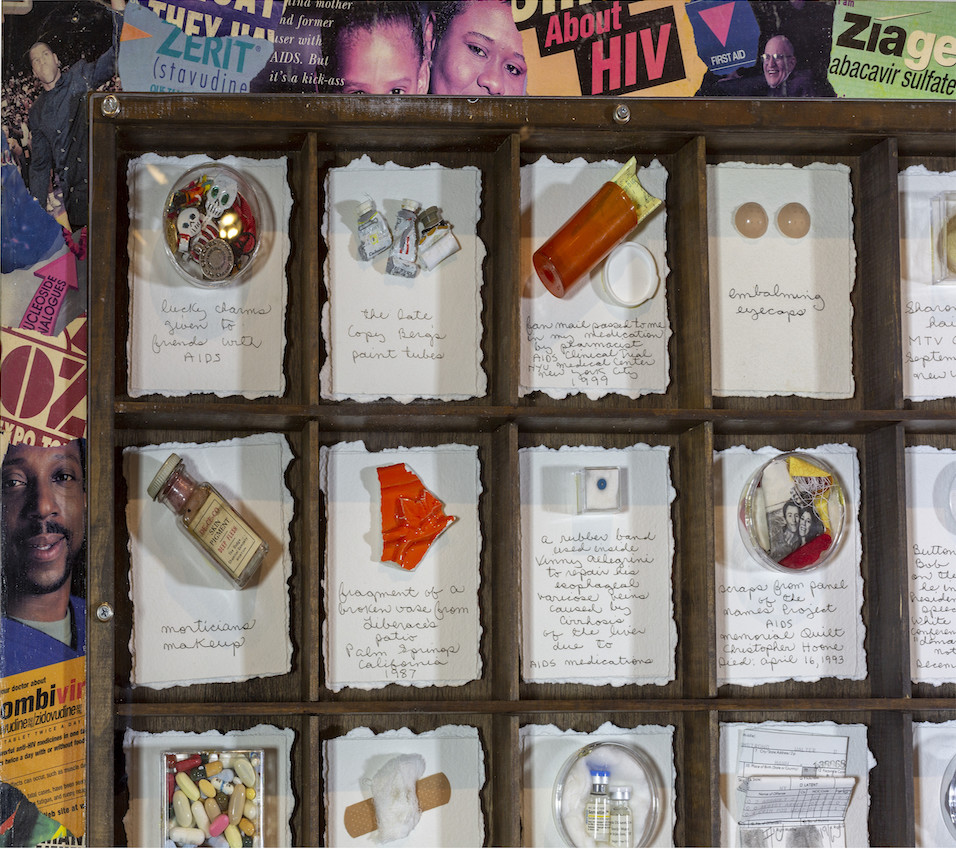

He often worked in the format seen in AIDS Museum (Reliquarium). Creating a gridded structure, he would fill each box with small objects, accompanied by descriptive hand-written labels. He called these structures “museums.” With the advent of the AIDS epidemic, and Benes’s own eventual HIV-positive status, he began utilizing objects related to the epidemic—medication, syringes, souvenirs of fundraisers, HIV-infected blood, and even cremated human remains.

He often worked in the format seen in AIDS Museum (Reliquarium). Creating a gridded structure, he would fill each box with small objects, accompanied by descriptive hand-written labels. He called these structures “museums.” With the advent of the AIDS epidemic, and Benes’s own eventual HIV-positive status, he began utilizing objects related to the epidemic—medication, syringes, souvenirs of fundraisers, HIV-infected blood, and even cremated human remains.

While a challenging work to spend time with, AIDS Museum’s rich and complex combination of text and image posed a unique opportunity for exploration in this particular course. Sam Ace put this eloquently: “In a most basic sense, a poem is made by gathering concrete details of experience and organizing them to form something larger than any one moment. In this piece, Benes has gathered and labeled personal objects and detritus of the AIDS epidemic: blood, surgical tape, a syringe, pills; and made them into a reliquary that is both a memorial and an elegy. The piece is a profound example of how text and image/object combine to form nothing less than poetry.”

On February 18, 2020, students in “Poetry and Image” gathered in the Museum for their seminar. The Benes piece presents difficulties for open-ended, inquiry-based close-looking, since its written elements give much away. In response to this challenge I gathered students further away from the work than usual, far enough that the words could not be deciphered, but close enough to make out the colors and shapes of objects. After around 20 minutes of conversation from this distance, students gathered closer to the work and began reading the descriptions they found under each boxed object:

On February 18, 2020, students in “Poetry and Image” gathered in the Museum for their seminar. The Benes piece presents difficulties for open-ended, inquiry-based close-looking, since its written elements give much away. In response to this challenge I gathered students further away from the work than usual, far enough that the words could not be deciphered, but close enough to make out the colors and shapes of objects. After around 20 minutes of conversation from this distance, students gathered closer to the work and began reading the descriptions they found under each boxed object:

Tape used in act up actions

Waiting room number from the New York City Board of Health Venereal Disease Clinic, 1971

Straw sucked on by Andrew Sullivan

Tile from Chelsea Gym steamroom, April 14, 1999, New York City

Cremated remains of Brenda Woods. Born: July 5, 1947. Died: Nov. 1, 1989 of AIDS

The students discussed the use of medical paraphernalia and its visceral impact on the viewer. They explored the meaning of combining objects associated with both celebrities and everyday people. They considered the importance of consent in the creation of an assemblage like this. I scaffolded the conversation by providing key pieces of information about the artwork and the artist in response to students’ observations and insights. We then turned to a discussion of the title of the work. Why call this a museum? What are the connotations of collecting in personal versus public spaces? The work’s subtitle, Reliquarium, was then revealed, leading to a conversation about Benes’s Catholic upbringing, the meaning of relics and reliquaries, and our own collecting of treasured objects. We discussed the nature of relics, realizing that taking, keeping, and treasuring small mementos from throughout one’s life is something almost all of us can relate to.

The students discussed the use of medical paraphernalia and its visceral impact on the viewer. They explored the meaning of combining objects associated with both celebrities and everyday people. They considered the importance of consent in the creation of an assemblage like this. I scaffolded the conversation by providing key pieces of information about the artwork and the artist in response to students’ observations and insights. We then turned to a discussion of the title of the work. Why call this a museum? What are the connotations of collecting in personal versus public spaces? The work’s subtitle, Reliquarium, was then revealed, leading to a conversation about Benes’s Catholic upbringing, the meaning of relics and reliquaries, and our own collecting of treasured objects. We discussed the nature of relics, realizing that taking, keeping, and treasuring small mementos from throughout one’s life is something almost all of us can relate to.

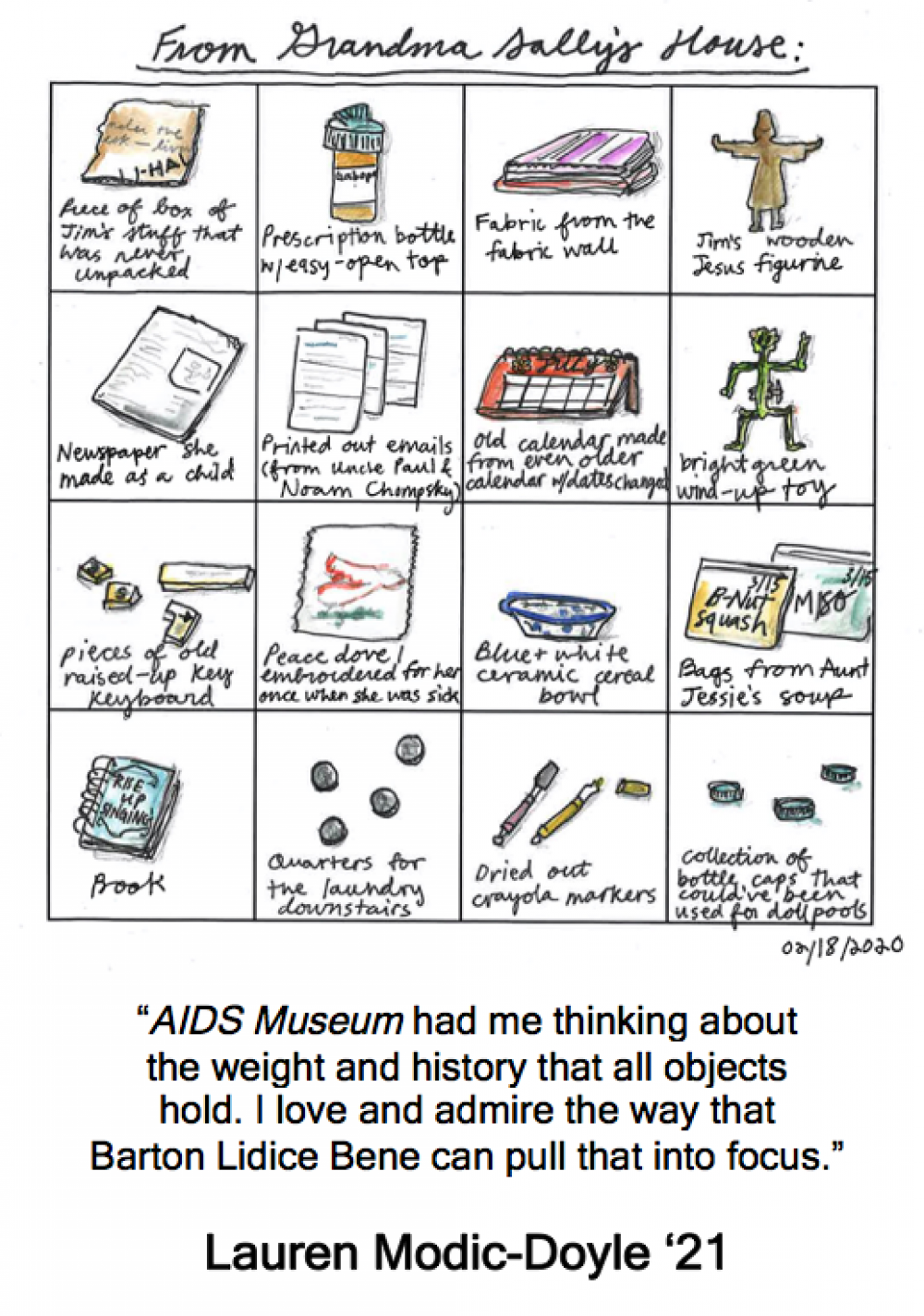

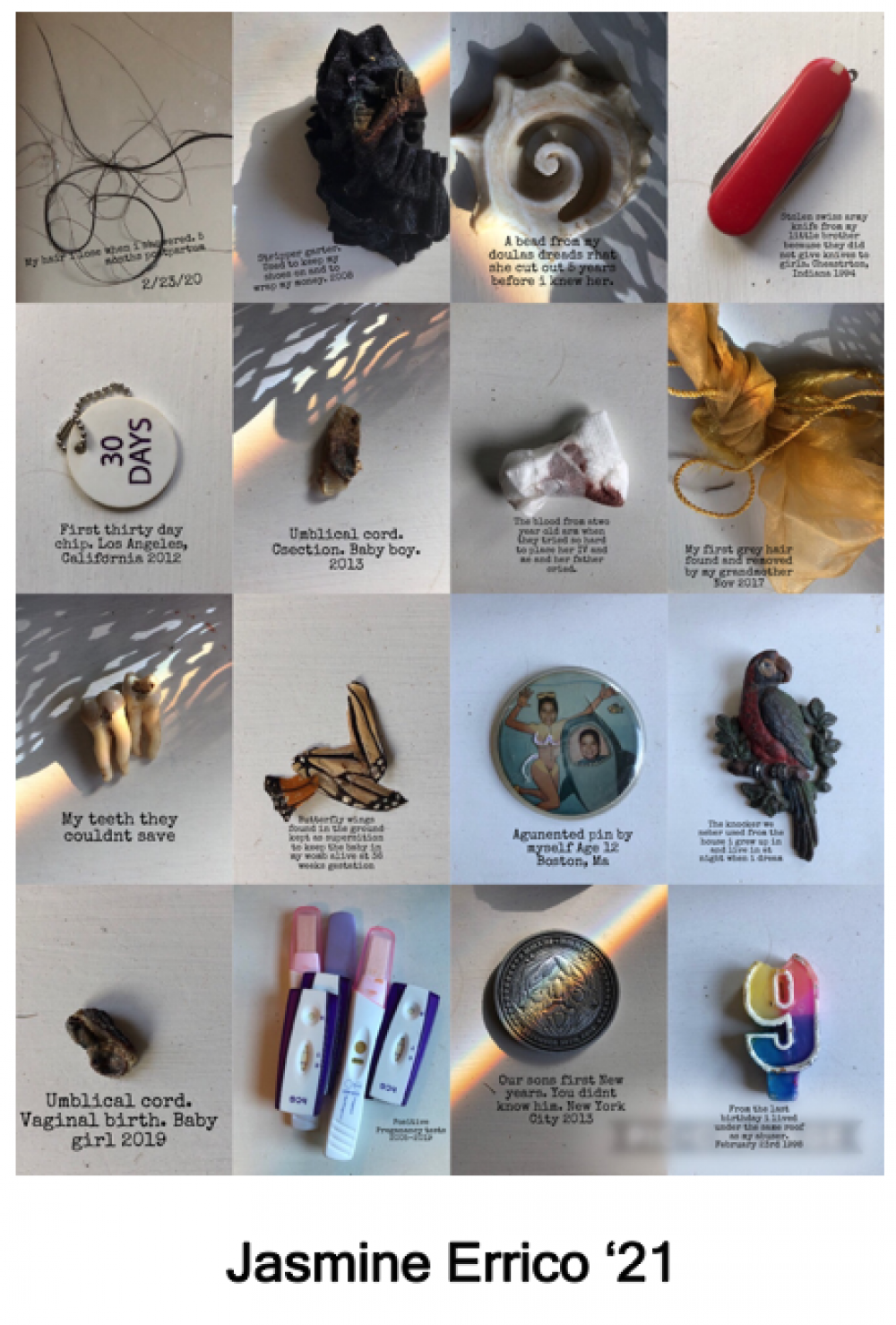

With this turn in the conversation towards the personal, I then provided the students with simple, gridded, sheets of paper and invited them to sketch out a reliquarium, or “museum,” of their own, complete with textual descriptions. They were asked to think about a moment in time, a place, a person, a community, anything that they might want to dedicate to a mini-museum. Many students continued this work after the museum session, some incorporating real objects and photographs, several of which can be seen in the class virtual exhibition on the Museum’s website.

Reflecting on the museum session, Sam Ace shared: “The opportunity to spend a significant amount of time considering the context out of which the piece was made, as well as the personal and historical implications of the collected objects, was very powerful. It allowed students to more deeply consider the details of their own histories and to create their own personal reliquaries.”

Reflecting on the museum session, Sam Ace shared: “The opportunity to spend a significant amount of time considering the context out of which the piece was made, as well as the personal and historical implications of the collected objects, was very powerful. It allowed students to more deeply consider the details of their own histories and to create their own personal reliquaries.”

Looking at this artwork in mid-February in Western Massachusetts, we touched briefly on the then distant-seeming coronavirus outbreak and in particular the stigmatization and prejudice that can accompany epidemics. Reflecting now on the session with “Poetry and Image” and the bright, insightful students who spent an hour with this compelling object, I am struck by the magic that happens when people are brought together around original works of art. While we continue to teach with art remotely, I eagerly look forward to returning to working with faculty, students, and physical artworks in the galleries of the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum.

GIVE

GIVE