Close Encounters with Frederic Leighton

For Curator Emerita Wendy Watson, a visit to the exhibition A Very Long Engagement: Nineteenth-Century Sculpture and Its Afterlives conjures memories of her many encounters with Frederic Leighton's 1890 sculpture The Sluggard. Watson, who facilitated the acquisition of a small bronze cast of The Sluggard for MHCAM in 1985, takes us from the Museum's galleries to an exhibition in Paris to Leighton's elaborate house and studio in London.

Close Encounters with Frederic Leighton

On a recent October day, I slipped into the Museum for an art infusion. As I opened the door to the first gallery, I was surprised to see that there was absolutely nothing on the walls.

There was a good reason for this, however: the gallery was completely filled with sculpture.

It’s not often that viewers get to see exhibitions devoted entirely to sculpture. Three-dimensional works of art can be difficult to handle and have complex installation requirements. And, in a word, they take up space. The Abstract Expressionist Ad Reinhardt is famously quoted as saying that “sculpture is something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting.”

But in MHCAM’s beguiling exhibition, A Very Long Engagement: Nineteenth-Century Sculpture and Its Afterlives, the focus is entirely on the carefully chosen objects arrayed around the room, beckoning to visitors undistracted by paintings. We are free to luxuriate in close-up viewing—unencumbered by Plexiglas vitrines—to move slowly around the sculptures, to notice the quality and vitality of their surfaces, and to take in their magic. The sinuous curviness of the installation itself and even the typeface of the labels further invites us to get into that reflective mood. And, a museum, of course, is the perfect place for musing.

It’s been a while since many of these works have been in the public eye, although they make cameo appearances in classes in the Museum’s teaching gallery. One of them has occupied a special place in my mind for many years: Frederic Leighton’s languorous bronze, The Sluggard, one of only two sculptures by this talented painter of the British Aesthetic movement.

First shown in 1886 at the Royal Academy (and now in London’s Tate Gallery, where I last saw it), the original life-size work caused quite a stir in the London art world. In fact, it proved to be a watershed in the history of the medium. Leighton was onto something new, successfully merging the exquisitely real with the classically ideal, and triggering a movement known as the “New Sculpture.” Charles Baudelaire’s 1848 critique of three-dimensional art in his own era—"Why Sculpture is Boring”—no longer applied.

Leighton’s first sculpture, The Athlete Struggling with a Python (1877), and then The Sluggard (also called An Athlete Awakening) were in great part responsible for this paradigm shift. As it turned out, The Sluggard deeply affected many art lovers of the time, and they clamored for smaller versions that they could call their own. Bronze and plaster versions of Leighton’s captivating nude—approved for circulation by the artist himself—took their place in Victorian homes alongside copies of ancient artworks seen on the Grand Tour. The artist was often pictured with one himself, and a smaller version even appears in the hand of a figure on his monumental tomb in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Leighton’s idea for this revolutionary sculpture was inspired by a surprisingly casual occurrence in his studio. After a long day of posing, his Italian model Giuseppe Valona, stood up, arched his back, stretched his arms, and gave a great yawn. Leighton immediately sat down and captured this image in a clay modello. Although it may have had its origins in life, there can be no doubt that Michelangelo’s Slave and Donatello’s David were not far from the artist’s mind.

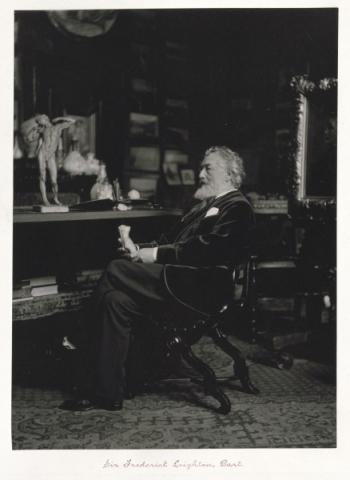

Lord Leighton P.R.A., ca. 1889-91, platinotype print mounted on off-white card, photo: R.A./Prudence Cuming Associates Limited. © Arthur Robin Winwood Tomkin, nephew of Margaret Winwood Robinson who was a daughter of Ralph Winwood Robinson

Not surprisingly, the original life-size bronze, an important embodiment of the British aestheticism and the New Sculpture, took center stage in the landmark exhibition The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900 of 2011-12. In Paris, where I was fortunate enough to see this show, I was more than pleased to be greeted by Leighton’s masterpiece, dramatically lit on a circular central pedestal.

When I visited London last year, I followed the strict instructions of a friend: “You must go to Leighton House.” She didn’t know about my fascination with The Sluggard, but it proved to be a perfect experience to bring my appreciation of Frederic Leighton full circle. Like several other successful artists, Leighton was able to build an impressive residence in Holland Park, a center of artistic activity in the city. He also opened it to the public on a regular basis as a “show studio.” Construction began in 1864 with architect George Aitchison, and Leighton moved in the following year when the first phase was completed. Soon, meticulously planned extensions were added to enlarge his studio but also to fulfil his architectural and artistic fantasies. Travel to “exotic” places like Turkey, Egypt, and Syria fueled the artist’s imagination and his desire to incorporate the many textiles, pottery, and other objects he had collected along the way.

It is almost impossible to describe this astonishing house and one’s experience of traveling through it. On a quiet leafy street behind an austere brick façade lies an unexpected fantasy world that includes a two-story domed Islamic-style courtyard and fountain, polished halls with marble columns and painted friezes, and a staircase bedecked with glittering mosaics, marbles, tiles, and a large stuffed peacock. Other rooms, tastefully outfitted with silk walls, serve as galleries for Leighton’s impressive art collection which included paintings by Old Masters and distinguished contemporaries like John Everett Millais and G.F. Watts. I once again encountered The Sluggard—this time the artist’s personal version—in his large well-lit studio where he painted and held regular social gatherings of artists, musicians, and friends.

Mount Holyoke’s own Sluggard continues to exert its power over me and I expect it always will. This perfect expression of the New Sculpture, inspired by the ancient and Renaissance past, never fails to surprise me with its remarkable spontaneity, elegance, and eloquence.

Give

Give