A Baker's Dozen: A Journey Through Food History with Museum Objects

In summer 2018, Clarissa Adan FP '19 conducted research on objects from the Joseph Allen Skinner Museum as part of her Lynk internship, which evolved into a culminating project focusing on the history of food. During her study of art and artifacts related to foodways, Clarissa discovered the fascinating history behind many under-researched objects in both the Skinner and Art Museum collections, revealing important insights into how different cultures interacted with this key aspect of human experience.

Food is life. This is true regardless of where or when you live. In fact, most of human history is traceable through the study of alcohol and bread. Studying artifacts and art associated with or depicting food can give us important insights into how people at different times and places interacted with this all-important resource. Let’s take a visual and chronological tour through the collections of the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum and the Joseph Allen Skinner Museum, thinking about food and human history.

1) Prehistory

In the late 1920s and early 1930s the American School of Prehistoric Research took students from several colleges, including Mount Holyoke, on excavations throughout France. On one of those trips, a 100,000-year-old hearth soil sample (2016.16.664), a cleaver (2016.16.227), and a proto audi point (2016.16.613) were found in Abri des Merveilles at Castel-Merle, France and brought back to MHC. When looking closely at the hearth soil sample, you can see bones and pieces of burnt wood from a cooking fire. Cooking and drying in the earliest hunter/gatherer societies both increased the nutritional benefits of their food and extended its storage life. This was important when food was entirely seasonal and relied on many factors out of their control.

2) Ancient Americas

North American indigenous groups became increasingly sedentary as they engaged in agriculture and sustainable foraging. Many cooking implements shifted from hide and gourd containers to carved stone bowls, which were the precursors to pottery. A steatite (soapstone) bowl (191.F) in the Museum’s collection was made between 3,000 and 1,000 BCE in the northeastern section of the United States. Bowls like this were used for both cooking and storage.

3) Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

The importance of agriculture to the growth of civilization is apparent through the artifacts left behind from Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Beer and bread were such critical methods of payment for royal messengers that their daily rations were recorded for posterity and they were some of the first mass-produced foods. The Museum’s ancient Egyptian bread mold (1909.16.A) was used for making small loaves. A Mesopotamian cuneiform tablet (2016.14.7) documents daily ration payments to royal messengers with the following inscription:

5 silas (1 = a bowl or cup) of beer

5 silas of bread

5 shekels (1 = ~1/2 ounce) of leeks

3 shekels of oil

2 shekels of soap.

4) Ancient Greece and Rome

As food security improved in the Mediterranean through agriculture, more time and effort could be devoted to creating luxury items like vessels to hold wine. A Greek wine cup, or skyphos, (1910.10.B.AIV) from the third or fourth century BCE is made of red clay with black glaze and painted decorations. A first-century Roman bowl (1937.27.C.K) reflects the rise of the art of blown glass , which became very popular with the upper classes at this time.

5) Americas, 1000–1600

The domestication of corn and chocolate in North, Central, and South American cultures was well established by this time. A stone metate (2016.10.17) like this one from Costa Rica, would have been used to grind corn or chocolate for easier cooking. A 16th-century canteen (SK K.129), now in the Skinner Museum, is an example of the kind of vessel produced by the Ancestral Pueblo peoples. This culture perfected the art of making pottery from the readily-available local clay in order to store, transport, and cook their food.

6) Renaissance Europe

To Feed the Hungry (2009.8.2a) and To Give Drink to the Thirsty (2009.8.2c) by George Pencz (German 1500-1550) are from the circa 1534 print series Seven Works of Mercy. Providing for the poor was important act of charity for a devout Christian. Images of food also appeared frequently in secular contexts. “Birth trays” (2018.23) were used to bring new mothers food and small gifts after giving birth. The scene on the Museum’s example shows a new mother lying in bed and eating off a similar tray covered by a linen napkin.

7) North and South America, 1600–1800

An Incan kero (A.E.1.1) from the early 1600s is highly decorated with scenes depicting the sacrifice of cattle. This object could have been used for ritual or everyday use. An expertly crafted but plainly fashioned hand-carved burl bowl (B.12.A.35.1), is probably from New England and was most likely used to serve food.

8) Colonial America and 18th century Europe

Before the expansion of trade routes in the late 1600s sugar, salt, and spices were extremely expensive. After supplies of these goods increased and the price dropped, they became common items in most kitchens and on many dinner tables. For many years nutmeg (B.11.A.91.1) was the most highly prized spice and aristocrats would bring their own decorated nutmeg graters to dinner parties. One such example from MHCAM dates from 1700 and is decorated with a tulip motif (1986.33.66). For centuries the availability of salt on your table showed one’s wealth and importance. The now-ubiquitous condiment was served in open dishes like the Museum’s salt cellar (1986.33.40a) from 1793.

9) Alaska, late 1800s

The traditional diet of Alaskan Natives relied heavily on fish and seals. The tools used for hunting these were often as decorative as they were functional. A halibut hook (L.G.4) is carved with designs intended to increase luck in fishing. Other objects, like this fishing spear (K.128) and knife (179.F), are more utilitarian. The knife, or ulu, was a women’s knife, used for everything from stripping blubber to sewing.

10) United States and Europe, 19th century

Expanded availability of spices and other “exotic” foods from European and US colonies changed how people ate. The better off you were, the more access you had to different flavorings. This special lemonade pitcher (1999.18.2) by Tiffany & Co., was given as a wedding present in 1895. Lemons and sugar were both expensive, so lemonade, which required both in large amounts,would have been only for special summer events. This condiment set (1986.33.25.1-5) from the early 1800s has cruets for oil and vinegar, mustard pots, and salt and pepper shakers. Like the lemonade pitcher, it is a demonstration of wealth and refinement in everyday life.

11) Oceanea, 19th and early 20th century

In Fiji, a traditional drink was made from the Kava root with mildly euphoric properties. Special kava bowls (E.12.A.35.4) were used in making large batches of the drink and were frequently passed down in families for generations. It wasn’t until 1778 that Europeans made contact with another Polynesian island and culture—that of Hawaii. Hawaiian poi pounders (like 1.19.V.B(a)) are used to make a traditional food staple from fermented and mashed taro roots.

12) Mount Holyoke, 1800s

In the early days of Mount Holyoke College, the students and most of the faculty ate their meals together. The willow pattern sauce tureen & lid (1975.3.22a-b), willow pattern platter (1975.3.19), and willow pattern caster (1975.3.10) were part of the original dining hall service from the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary and continued to be used through the early years of the College. The Chinese influence seen in the decorative pattern was very popular during the period. The food served on them would have been simple standards like bread and stews found in many New England kitchens.

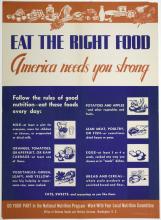

13) The United States, mid-20th century

The US government started publishing nutritional recommendations in the late 1800s. During World War II the Department of Defense published a nutrition poster with the directive “Eat the Right Food, America Needs you Strong” (2000.577.33.INV). It was aimed at keeping the citizens at home healthy, so they could continue working in factories, and growing food to supply the troops. In 1945 and 1946, Wayne F. Miller (1918–2013) received two consecutive Guggenheim fellowships to take a series of photographs in the South Side of Chicago. Many of the images centered around food and drink. Rabbits for Sale (2012.18.8) for example, shows a line of rabbits hanging above a sidewalk waiting to be purchased.

The next time you are out with friends and family, sharing a drink, and enjoying a good meal—you can think about how you got there. During the 100,000 plus years covered by these objects and works of art, there have been dramatic changes in food and food culture. At the same time, so much of it has also stayed the same. The times and places might be different, but food and drink will always bring people together.

Give

Give