A 19th-Century Turkmen Asmalyk

In this Objects of Our Affection post, Associate Curator of Education Kendra Weisbin weaves together the history of a beautiful 19th-century textile—a 2017 gift to MHCAM—and her own cultivation as a specialist and enthusiast of Islamic carpets.

A 19th-Century Turkmen Asmalyk

This summer MHCAM acquired a small but strikingly beautiful nineteenth-century Turkmen weaving, a gift of Walter B. Denny, professor of art history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Serendipitously, the weaving’s placement at MHCAM completes a circle in my own art-historical education, and makes me reflect on how my love of Islamic carpets began.

Like most people, I never thought of carpets as anything more than decorative floor coverings, until I spent the summer of 2002 interning in the Asian and Islamic art department at the Brooklyn Museum. The department had hired a carpet expert to thoroughly review and catalog each rug in the collection. I was expected to attend the full week of review, eight hours a day, and take notes on everything the expert said. I was twenty years old, desperate to do well, and somewhat in awe of the very idea of an expert, a connoisseur.

This expert interacted with art in a way I had never seen before. He practically spoke to the carpets, showing how, just by looking and touching, one could tell a story about the rug and who made it: stroke the pile to determine where the weaver started her work; pinch the fringe with your fingers and count the yarns (3 yarns instead of 2 and you’re looking at a Caucasian carpet); run your finger over the brown wool—feel the corrosion, the lower pile, a result of the iron mordant in the dye; push the pile back ever so slightly to see the structure of each individual knot—find a symmetrical knot and your rug is from Turkey, the Caucasus, or Senneh in Iran, find an asymmetrical knot and your rug is probably Persian or Central Asian.

He spoke about the weavers as individuals—something scholars rarely do with works by unknown makers. He hypothesized about each woman’s design choices, her experience weaving (and thus how old she was), and pointed out places in the rug where you could see she made a mistake or changed her mind. He demonstrated how to pick apart the dizzying array of patterns and designs skillfully, piece by piece and color by color. I was enthralled.

That inspiring expert was none other than Walter B. Denny. I later sought out Walter to pursue my graduate studies at UMass. Now, almost 15 years later, after gifting this weaving to MHCAM, he asked me to perform the same kind of analysis on it that I had first watched him do at the Brooklyn Museum. What stories could this weaving tell us?

A Closer Look

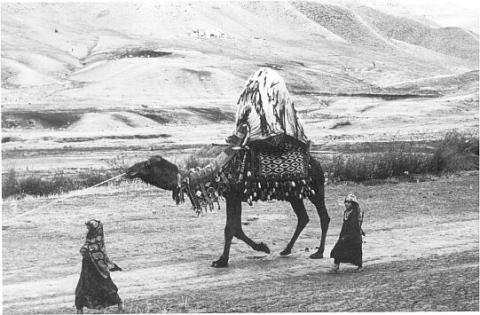

The field is comprised of five wide stripes filled with stylized tree or plant designs, and geometric motifs fill the numerous borders. And what about the intriguing shape of the weaving? Its unusual pentagonal format with triangular top indicates its function as an asmalyk, a camel trapping thought to be woven specifically for use in wedding processions. They were woven in identical pairs and hung on either side of the camel ridden by the bride to her new husband’s home. The asmalyk would be attached to the camel or bridal litter by the two braided ropes attached to the top right and left sides of the weaving (only the left rope survives in our example).

Yomut bride on camel bearing an asmalyk and other trappings. Photo: William Irons

The piece is technically precise and skillfully, tightly knotted—a hallmark of Turkmen weaving. The Turkmen are a Central Asian Turkic people, primarily living in Turkmenistan, but also present in the Caucasus, Iran, Afghanistan, and other neighboring regions. There are six major Turkmen tribes: Tekke, Yomut (also called Yomud), Salor, Ersari, Chowdur, and Saryk. The design of the weaving can give us clues, but a closer look at the knot structure will help us discover which of these six tribes made this particular trapping. Pinching apart the pile to reveal each tiny pixel that makes up the carpet’s design, we see symmetrical knots—a sign of Yomut weaving. Examining the weaving’s individual yarns reveals z-spun wool (seen in almost all Islamic rugs), which likely would have been sheared, carded, spun, and dyed by the family or Yomut community that the weaver belonged to.

Despite its intricate design, the carpet’s color palette is deceptively simple: red, orange, dark brown, medium brown, blue, and white are the only colors used here. The red and orange are derived from madder root, a plant that could be obtained locally and which produces a wide variety of colors depending on what mordant is used, as well as the temperature and acidity of the water. As we look more closely at the carpet we notice that the blue wool displays subtle variations in color—shifting from dark to medium to light blue. Is this a mistake in the weaving, an aesthetic choice, or the effect of fading over time? These color variations are known as abrash: when wool is dyed by hand in small batches minor differences in color occur naturally. Weavers often use this effect to their artistic advantage, arraying hues to form a cascade of color that seems to almost shimmer in the light.

In Turkmen culture (and many others) weaving is a woman’s art, and this asmalyk would have been woven by a woman, probably the young woman whose bridal litter it would decorate. As an object associated with wedding processions and dowries it has connections to many other objects in the Museum’s collection, including a Renaissance cassone (2008.13), a Hadley chest (1923.2.I(b).SIV), and even a pair of Japanese screens depicting the Tale of Genji (1972.26.Q.PI).

The Museum is grateful to Walter Denny for this generous gift, which will enrich our object-based teaching at MHCAM. And I am grateful for the chance to use this weaving to spark the imaginations of a new generation of carpet-lovers at Mount Holyoke.

Give

Give