Counter Stories: Art Reframed

A'mara Braynen '22

Student Guide, Spring 2020

“History continues into the present and implicates persons still alive.” -Richard Delgado & Jean Stefancic, Critical Race Theory (Third Edition)

people_2019fa_stud_guides_oct18_v003-scr_banner.jpg

Laura Shea

Introduction

We as humans share history collectively but contribute individually to the fabrication of particular narratives. Our history travels with us and I’d like to challenge conventional understanding of the dominant narratives we inherit.

We as humans share history collectively but contribute individually to the fabrication of particular narratives. Our history travels with us and I’d like to challenge conventional understanding of the dominant narratives we inherit.

This analysis of MHCAM’s collection is entitled, "Counter Stories: Art Reframed." In this exploration we will ponder the implications of fictionalized narratives for marginalized groups. Viewing art as a medium to challenge conventional frameworks of history allows a fresh perspective, especially as we do it collectively, cooperatively...united.

Our goal is to engage in the understanding of personal stories through an empathic and subversive framework. My hopes are that after traveling through time and looking closely at art we will begin to cultivate a curiosity about the production of history and how “history continues into the present and implicates persons still alive” (Richard Delgado & Jean Stefancic, Critical Race Theory [Third Edition]).

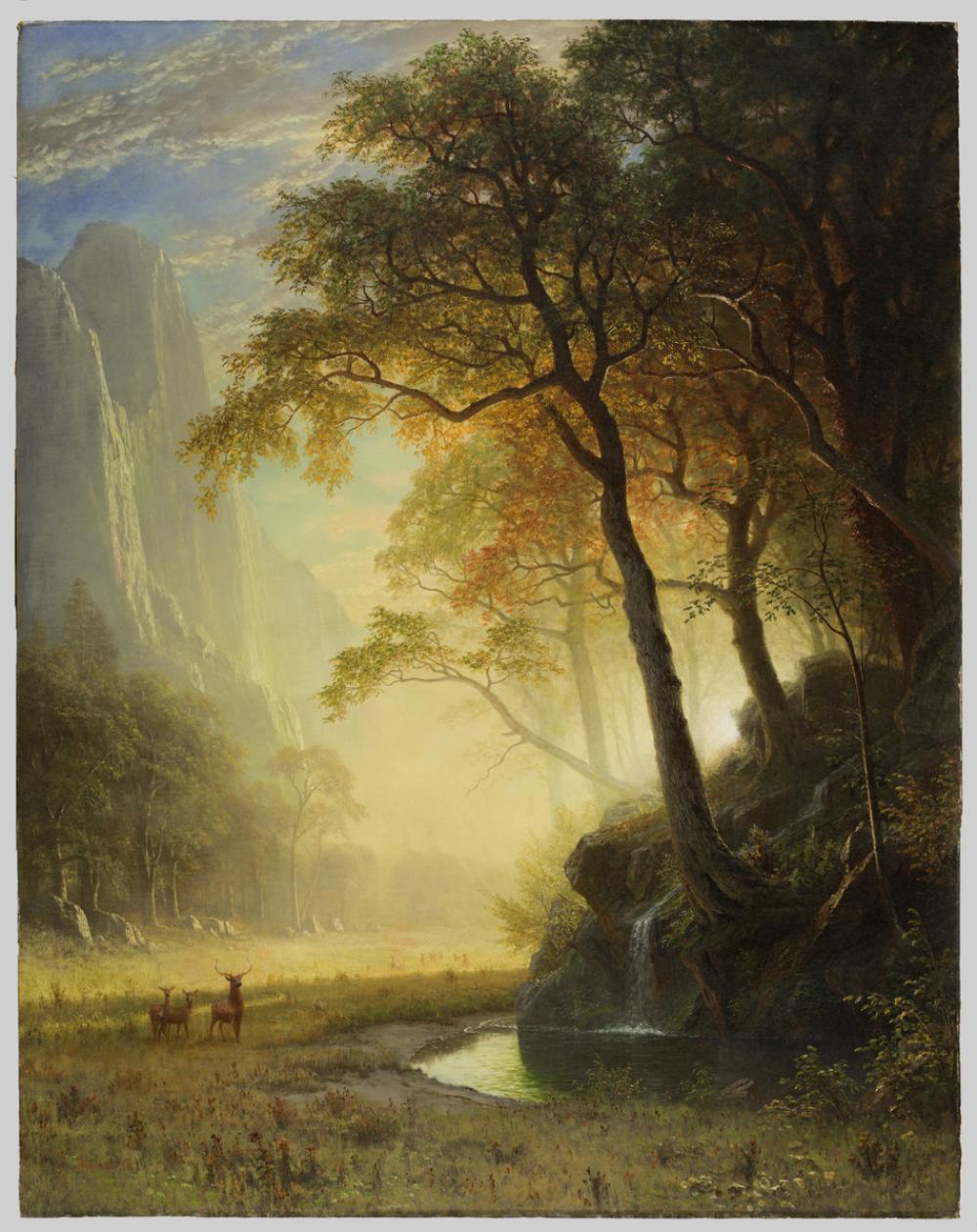

1. Hetch Hetchy Canyon, 1875

Albert Bierstadt (American, b. Germany 1830-1902)

oil on canvas

Gift of Mrs. E. H. Sawyer and Mrs. A. L. Williston

MH 1876.2.I(b).PI

This painting of Hetch Hetchy Canyon was created in 1875 and was the first gift to the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum upon its opening in 1876. Try to look closely at details like color and composition. What time of day do you think it is? What season? Where do your eyes travel first?

It was painted by Albert Bierstadt, best known for his sweeping landscapes of the American West. He joined several journeys west to capture the breathtaking wonders of the seemingly untouched landscapes in his paintings.

Hetch Hetchy's extensive meadows were the product of millennia of collaborative management by Native American communities. For centuries, the Miwok and Paiute subjected the valley to controlled bushfires, preventing the forest from taking over the valley meadows. Providing ample space for the growth of the grasses and shrubs as well as additional room for large game animals to forage, like the elk you see in the foreground of the painting.

Motivated by the ideology of Manifest Destiny, European settler colonists invaded Indigenous homelands. “Cultural clashes” and “land disputes” are euphemistic ways of retelling North American Indigenous histories but the Indian Wars of 1875 resulted in the senseless slaughter of Native people and death as a result of widespread infectious disease.

When we consider the lack of visibility and representation Indigenous peoples still endure today, including inaccurate representation in history books and popular media, being untethered/uprooted from homelands, and a lack of Indigenous perspective in the retelling of history in the United States, we have to acknowledge the intentional erasure of their voices from the mainstream narrative of American colonial violence and domination. The erasure of Indigenous Americans through the process of history-making is not accidental and their absence within Bierstadt’s beautiful depiction of the Valley is not coincidental.

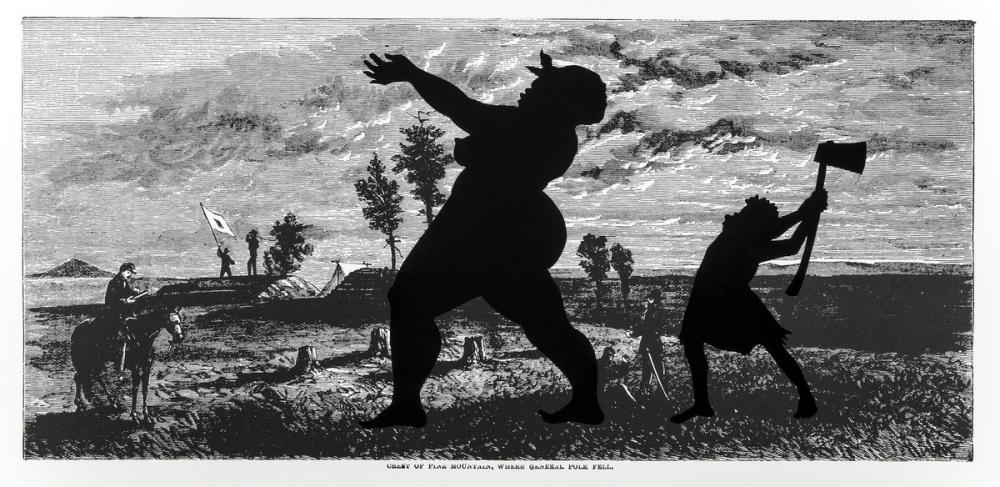

2. Crest of Pine Mountain, Where General Polk Fell

from the series Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) 2005

Kara Walker (American, b. 1969)

offset lithography and silkscreen on Somerset textured paper

Purchase with the Susan and Bernard Schilling (Susan Eisenhart, Class of 1932) Fund and the Belle and Hy Baier Art Acquisition Fund

MH 2012.14.7

The American Civil War (1861-1865) took place about a decade prior to the Indian Wars of 1875. In this work, contemporary artist Kara Walker takes an image published by Harper’s Magazine during the Civil War and alters it, placing her own silhouettes over it. There are two tall pitch black silhouettes in the foreground and comparatively miniscule soldiers around them. The large black silhouettes are clearly bodies, but the identities are ambiguous and suggestive. The motions or actions of these kinetic figures seem almost exaggerated.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) took place about a decade prior to the Indian Wars of 1875. In this work, contemporary artist Kara Walker takes an image published by Harper’s Magazine during the Civil War and alters it, placing her own silhouettes over it. There are two tall pitch black silhouettes in the foreground and comparatively miniscule soldiers around them. The large black silhouettes are clearly bodies, but the identities are ambiguous and suggestive. The motions or actions of these kinetic figures seem almost exaggerated.

Behind the silhouettes we see a scene from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War. Upon the ascent of Union soldiers at the peak of Pine Mountain, a stray bullet hit the Confederate general Leonidas Polk, killing him immediately.

Kara Walker’s silhouettes uses the legacy of slavery to penetrate the pristine historical narrative of the Civil War presented in Harper’s. Walker is well known for her art that visualizes and explores identity, race, sexuality, gender, and violence. She has described her work as visual representations of what it means “...to externalize what cannot be processed internally....”

Today, where we see the central female figure in Walker’s print, there is a tall monument on the site that commemorates the Confederate general. Wherever there is a Confederate general or soldier whose courage on the battlefield is honored, there is generational trauma contained in Black bodies that loom over and haunt these memorials and our collective memory in the present. Kara Walker purposefully “annotates” Harper’s narrative by imprinting her dark black silhouettes front and center. Walker does this to interrupt the neat order of the pictorial history of the Civil War, with a message that the legacy of slavery has not been erased by battles and blood, it is not stagnant in our past, but very much a part of our present.

3. The Harvest, 2018

Harmonia Rosales (American, b. 1984)

oil on linen and 24k gold leaf

Purchase with the Belle and Hy Baier Art Acquisition Fund

MH 2019.38

This extraordinary painting by self-taught artist Harmonia Rosales entrances us with beautiful Neoclassical imagery. Center stage, slightly elevated and in between two wine-colored columns sits a woman. Her expression can be read as tranquil, undisturbed, serene as she rests with a gaze focused downward and tall posture against a beautiful bronze-orange metallic background.

This extraordinary painting by self-taught artist Harmonia Rosales entrances us with beautiful Neoclassical imagery. Center stage, slightly elevated and in between two wine-colored columns sits a woman. Her expression can be read as tranquil, undisturbed, serene as she rests with a gaze focused downward and tall posture against a beautiful bronze-orange metallic background.

Topless, with her head adorned by a sheer veil, black halo and deeply pigmented red cloth draped across her lap, three brown babies huddle in her embrace and two brown babies rest at her feet. The baby with the deepest shade of melanin, complementing that of this mother-like figure, is slumped in her gently placed left arm fast asleep. The baby by her right foot is cocoa-colored with coiled black hair and leans comfortably against two books, making eye contact with a snake at the base of the step. The palest child on the bottom left sits in a somewhat protective stance, knees up to chest, clutching a loose string of pearls, staring directly forward. Look into her eyes, what do they convey to you?

More than mere reproductions or insertions of blackness into this style of European artwork, her intent is to reconceive idealized beauty and womanhood in a more harmonious way. The Yoruban words Ife (considered a holy city and birthplace of mankind), Enitan (person of story), Alkebulan (ancestral name of Africa), and Asaase Yaa (earth goddess of fertility) adorn the halo around the woman’s head, emulating female empowerment and cultural acceptance of Rosales’ West African heritage.

Afro-Cuban American artist Harmonia Rosales depicts and honors the African diaspora in all of her artwork. Transcending the canvas, her collections offer us an alternative visualization of history centering glowing, royal, magnificent Black womanhood. Reimagining and appropriating the aesthetics of old master European paintings, her work counters the Eurocentric beauty standards present in common depictions of the Virgin Mary, Eve, and other traditional Renaissance subjects. Rosales’ Harvest was made in the likeness and image of Charity, a painting by French Neoclassicist William-Adolphe Bougureau in 1878.

4. Black Heart, 1996-1997

Mary Ann Unger (American, 1945-1998)

Hydrocal (Plaster of Paris), fiberglass mesh, cheese cloth, shellac, pigments, diluted beeswax, graphite powder

Purchase with funds from Marion and Alan Brown

MH 1998.18

Mary Ann Unger, American sculptor and Mount Holyoke Alumuna (Class of 1967), created Black Heart between 1996 and 1997. The stone-shaped structure was created with hydrocal, a plaster of Paris and Portland cement mixture used for casting sculptures. Diluted beeswax, shellac pigments, fiberglass mesh, cheesecloth, and graphite powder coat the surface of this sculpture adding texture and shine.

Mary Ann Unger, American sculptor and Mount Holyoke Alumuna (Class of 1967), created Black Heart between 1996 and 1997. The stone-shaped structure was created with hydrocal, a plaster of Paris and Portland cement mixture used for casting sculptures. Diluted beeswax, shellac pigments, fiberglass mesh, cheesecloth, and graphite powder coat the surface of this sculpture adding texture and shine.

There is an understated embodiment of emotion in this work, as there is in much of her art. Her signature is abstractness and her sculptures are large in scale—often referencing bones, bandaged limbs, and flesh. They are usually dark and bulbous.

Unger was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1985 and subsequently passed away in 1998, a year after this sculpture was made. Thus, the ripped and torn mesh material on the sculpture’s surface can be seen as symbolizing her own physical distress and anguish. Her art reveals her individualized pain and also draws in others to experience her emotions, promoting critical thinking about broader physical manifestations of grief.

Unger’s Black Heart evokes the suffering and tragedy associated with her final year battling breast cancer. This sculpture may act as an imagination of a heart ache for us. In relation to the theme of conjoined histories, Unger encourages us to relate to one another through empathy and her own vulnerability. No matter what lens we view art through, sharing our personal experiences reminds us that we’re connected and in unity we each can contribute to radical acceptance and change in our world.

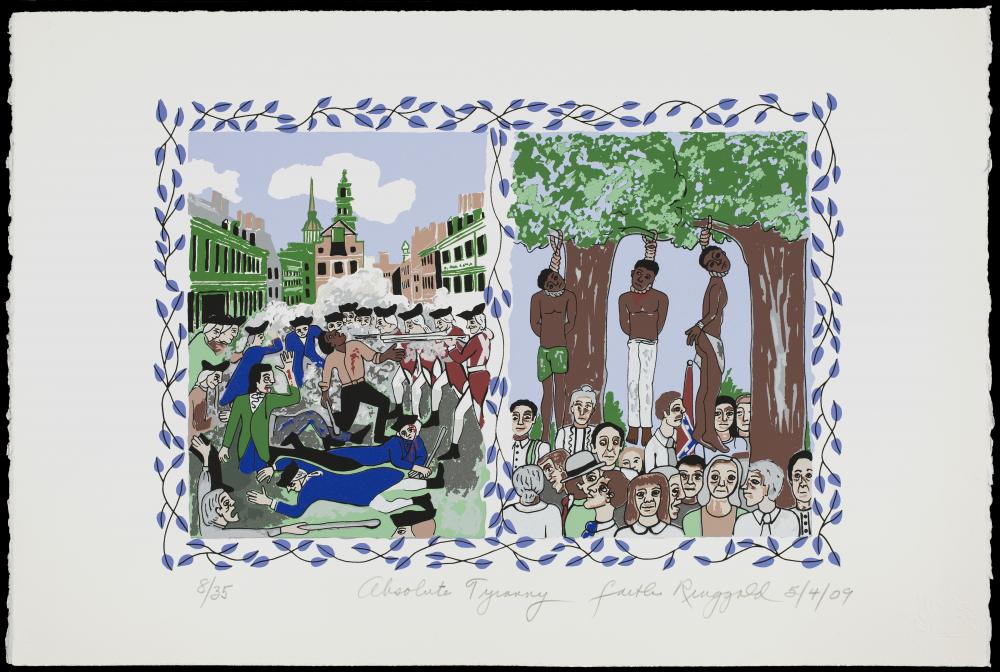

5. Absolute Tyranny (from the portfolio Declaration of Freedom and Independence) 2009

Faith Ringgold (American, b. 1930)

screenprint

Partial gift of the Experimental Printmaking Institute, Lafayette College and purchase with the Susan and Bernard Schilling (Susan Eisenhart, Class of 1932) Fund

MH 2016.2.12.1

Faith Ringgold is an artist and activist for the visibility and representation of African Americans and women. Absolute Tyranny is one of eight prints in a portfolio entitled, Declaration of Freedom and Independence, created in 2009.

Faith Ringgold is an artist and activist for the visibility and representation of African Americans and women. Absolute Tyranny is one of eight prints in a portfolio entitled, Declaration of Freedom and Independence, created in 2009.

We see two distinct scenes, each with highly saturated green, red, brown and blue pigments, surrounded and divided by blue vines. We see a lynching scene, Black male bodies swaying in trees (right) juxtaposed by popular imagery of the Boston Massacre (left) as colonial tensions rose, leading to the onset of the Revolutionary War.

Who is allowed to resist, to have the audacity to demand freedom from violence and oppression? In the late eighteenth-century, the Boston Massacre occurred when colonial subjects clashed with British soldiers. Was it not their right to demand and fight to live lives free from absolute tyranny under British rule?

Nudging us onward in history, across the blue leafy border, Ringgold gives us insight into twentieth-century lynchings, a violent and racist response—primarily in southern states—to financial crises as former slaves were no longer a source of capital. Was it not within the rights of Black Americans to live lives free from the tyranny of white supremacy?

The title and imagery of Faith Ringgold’s work evokes a particular political message, similar to the actual Declaration itself. It is imperative for Ringgold to bring to our attention, graphically, that all men on either side of this historical reproduction are not created equally or allotted the pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness that the Declaration of Independence commands.

The colonies were hypocritically founded on fictitious notions of racial essentialism and the toil, enslavement, exploitation, and murder of African and Indigenous peoples. Ringgold’s intentional pairing of the interconnected periods of time between African Americans and American colonists highlights and reveals the incongruity in the foundational framework of the Declaration of Independence.

We are challenged by all of these artists to look and be aware of our past and present circumstances as humans who all breath, feel, and perceive. My hope that is in looking at these artworks we may remember that there is always more to the story.

Give

Give