Tango for Page Turning Exhibition Guide

This online guide, written and designed by 2017 Institute for Curatorial Practice Intern Sylvie Mayer, provides descriptions, contextual information, and analysis of William Kentridge’s single-channel video projection Tango for Page Turning, on view in the Gump Family Gallery from September 5–December 17, 2017. The guide includes stills from the video, as well as photographs of Kentridge’s larger collaborative installation project, The Refusal of Time.

INTRODUCTION

“Breathe…wait a minute…breathe” says William Kentridge. This is how we measure time’s passage: through sensory experiences like breaths and footsteps, in sometimes steady and occasionally faltering rhythms. Though each individual experiences time differently, we all rely on ticking clocks for guidance. A continuum is broken into digestible hours, accommodating lives which rely on standardized time for scheduling, attending meetings, taking classes and catching trains.

Developments in physics, including Einstein’s theory of relativity and string theory, have altered conceptions of time. The certainty of a universal measure of time has been revealed as a construction, guided in part by political powers, and neither as stable or impartial as clocks suggest. Even with its abstract instability, time is something that many wish to grasp—or even halt.

South African artist William Kentridge (b. 1955) has meditated on time over the course of a collaborative project with scientist Peter Galison, composer Philip Miller, dancer and choreographer Dada Masilo, and an extensive production team. In his work, Kentridge assesses theoretical physics and resists colonial control of world time-keeping. He considers time as a rhythmic and perpetual “dance toward death,” with cycles of action and regret, longing and connection, and harmony and discord. These ideas have coalesced as a series of multi-media projects: drawings, projections, sculptures and soundscapes populate the rich layered installation The Refusal of Time, as well as the experimental opera Refuse the Hour.

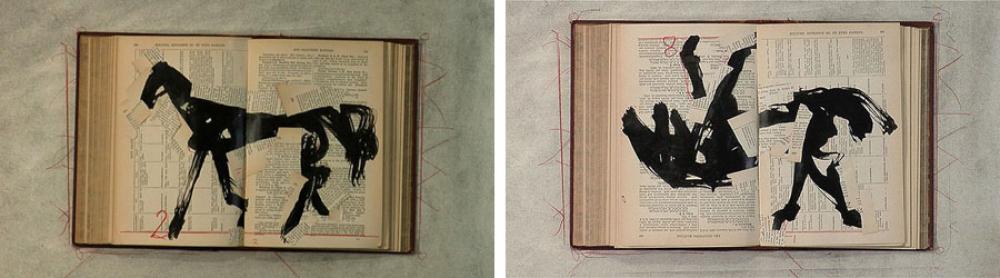

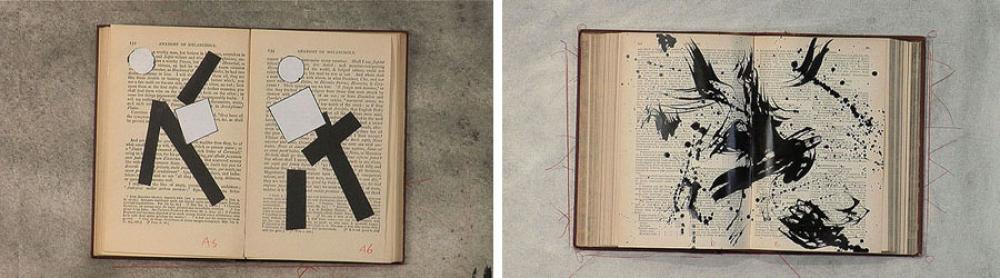

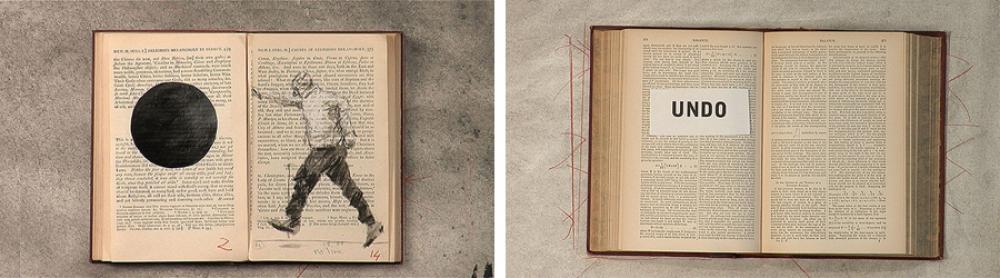

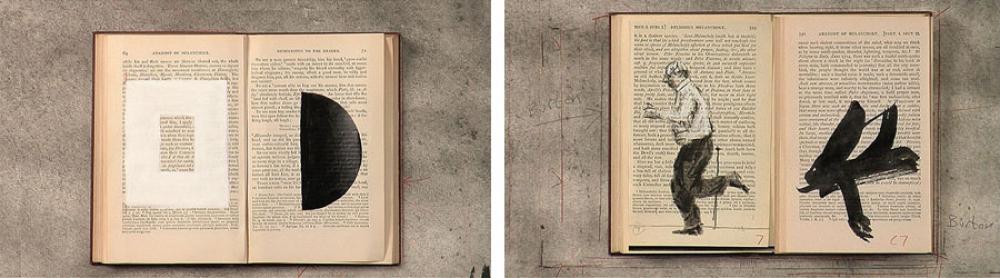

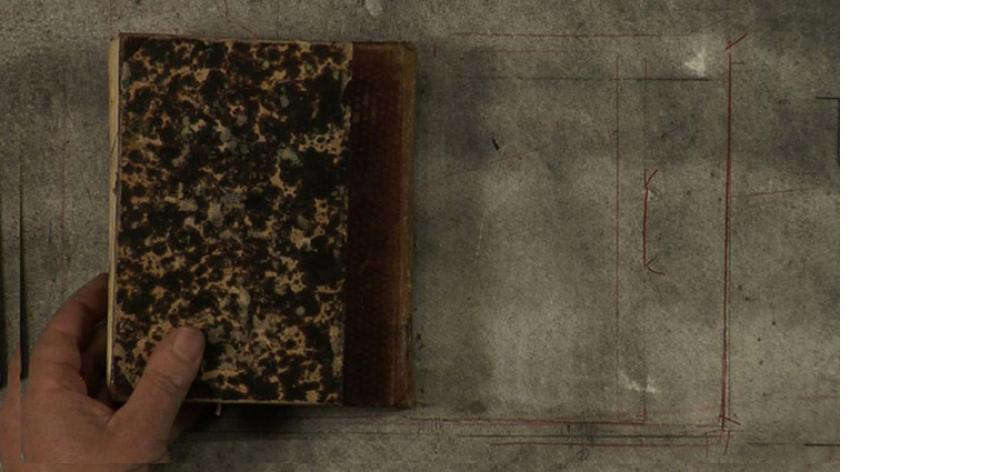

Tango for Page Turning (2012–13) is a 2 minute, 48 second film that is a part of the saturated world of Refuse the Hour. The work allows for an intimate engagement with time through the turning pages of an old book. Kentridge’s hands open a Dictionary of Applied Chemistry and the pages turn rapidly. Text devolves into spatial composition and annotations provide a story on redacted pages. Splotches and spills reference chaos and accident; figures run in place, interact, dance and spin; symbols, shapes and phrases flash across the pages, leaving traces—memories in a constantly moving progression.

Tango for Page Turning characterizes William Kentridge’s process-oriented, interdisciplinary practice. As a meeting place for art, science, dance, sound, and daily experience, the film is an appropriate first acquisition for the New Media Arts Consortium, a collaborative of the museums at Bowdoin College, Brandeis University, Colby College, Middlebury College, Mount Holyoke College, and Skidmore College, founded in 2016. The film supplies a starting point for further inquiry into collaborative processes and time as it relates to political history and physics.

William Kentridge (South African, b. 1955), Machine Room, Still from The Refusal of Time. © William Kentridge; photo courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery

William Kentridge (South African, b. 1955), Machine Room, Still from The Refusal of Time. © William Kentridge; photo courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery

William Kentridge (South African, b. 1955), Machine Room, Still from The Refusal of Time. © William Kentridge; photo courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery

PROCESS: COLLABORATION AND COLLAGE

Different elements, different causes and impulses come together to make a final meaning

—William Kentridge

The making of Tango for Page Turning, like all of Kentridge’s projects, involved developing connections through an intuitive process. He works without a clarified objective, instead, using the physical act of gathering and transforming material to generate ideas. “Do the work,” Kentridge says, “then see what it is that you have made.”

In the film, Kentridge unites his varied interests into an encompassing method, where sound, image, science, and dance interact. Each collaborator and production team member for Tango for Page Turning provides a contribution to a grand collage. Kentridge refers to this practice of collage as “fragmentation and reassembly” – a metaphor for how we make sense of the world. We are presented with bits of incomplete information, which we arrange to form our individual understanding of an immeasurably nuanced and complex reality. Piecing-together is a method for finding meaning in the vast channels of information that we must navigate.

MOVING IMAGE

An action and a history could be contained in rolls of film, in strings of images waiting to be reeled in, and long forgotten predictions re-examined.

—William Kentridge

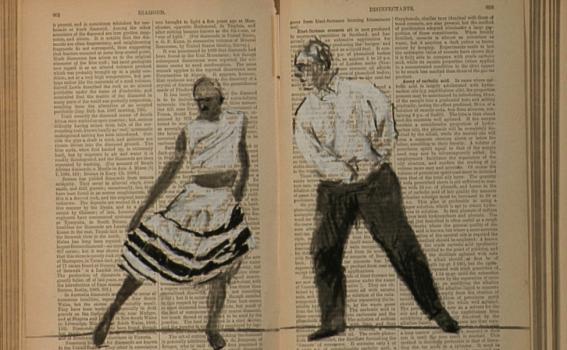

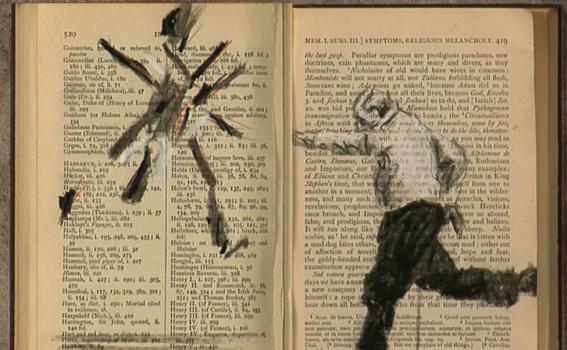

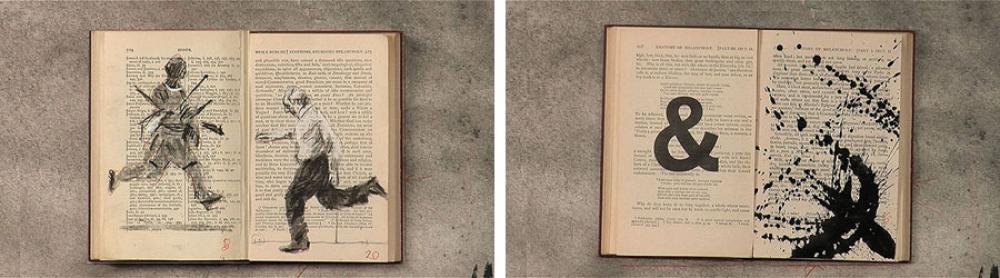

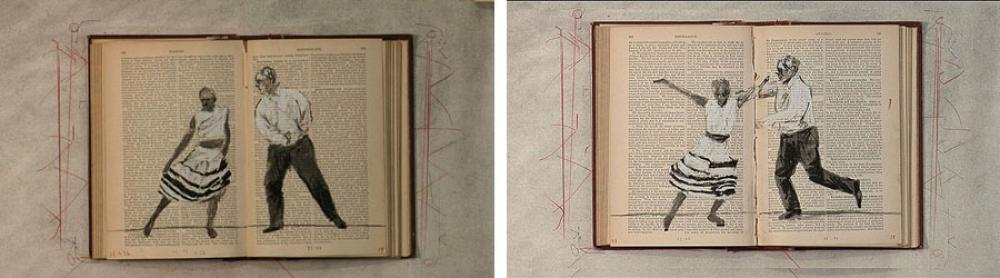

In Tango for Page Turning, an old book acts as a site for the construction of a film, where layers of collected media are introduced to form a whole. Drawings and phrases typed on white paper, including ‘particular collisions’ and ‘life & the transmutation of atoms’ float across the book’s yellowed pages. Numbers and lines in red chalk measure the movement of charcoal figures. Meticulously painted circles, squares, ampersands, and parentheses flash rapidly, interspersed with ink splotches reminiscent of Rorschach tests. The images of dancing figures and geometric shapes are clear, while the text behind them becomes obscured.

Unlike in a commercial animation studio, Kentridge’s technique does not involve storyboarding. A single drawing can serve as a starting point. He alters the drawing through erasure and addition, leaving traces of the former image behind to visualize what he calls a “process of vision and revision.” This unfolding is a part of Kentridge’s conceptual message: that the world is dynamic, always in motion and in a state of becoming, rather than static or final. His acknowledgement of the temporary lends itself to time-based media, since still drawings cannot show changing states.

In an animation, still images are strung together to create continuity. Kentridge believes that we experience the world in frames per second, so the construction of an animated film reflects how we establish our own perceptions. This relates to early motion picture inventions, which used spinning devices to move drawn images rapidly, creating a sense of motion.

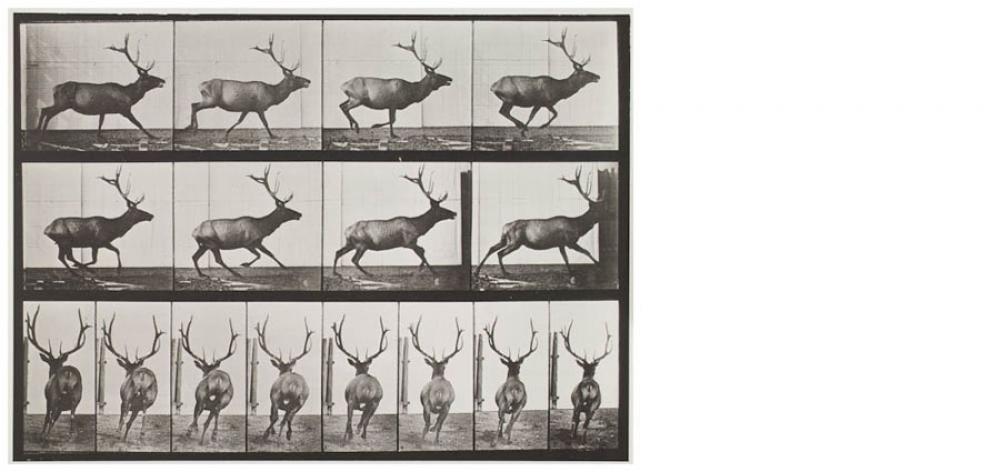

Kentridge engages with this history in Tango for Page Turning when a horse made of torn paper appears across the pages of the book, walking at a measured cadence. Kentridge is likely referencing Eadweard Muybridge’s studies in animal locomotion. In 1877, Muybridge was commissioned to take photographs of a running horse to settle a bet regarding whether all four of its hooves would leave the ground at the same time. Through these images, Muybridge demonstrated photography’s ability to capture and replay motion. In Kentridge’s film, as soon as the horse is stabilized, it is rearranged into nonsense, inverted and mismatched to deny the original analytic application of the animal locomotion studies.

Eadweard Muybridge, Animal Locomotion, Plate 695 (running elk) 1887, Collotype on ivory wove paper, Gift of Professor David Batchelder, 1971.1.I(b).RI.

SOUND

Can we use sound as a metaphoric representation of time?

—Philip Miller

Whether a composition is synchronized or in tension with its visual counterpart, music influences how images are perceived and interpreted. Sound annotates, creates mood, and drives narrative. Whether measured in phrases of rhythm, or the entire duration of a score, music operates across time.

In Tango for Page Turning, a fluid and familiar piano composition is layered with a fuzzy recording of an English translation of 19th-century composer Hector Berlioz’s La Spectre de la Rose, performed by vocalist Joanna Dudley. The stuttering and repetitious soundscape was developed by Philip Miller (b. 1964), a composer from Cape Town, South Africa who has been a long-time collaborator of Kentridge, developing scores for some of his earliest films.

Miller relishes the moments between vocalization, including breaths and tongue clicks. Emphasis on these accidental noises calls attention to sounds that people often filter out. Miller notes that his process is similar to Kentridge’s method for making visual compositions. His preliminary stages involve collecting sounds to later collage and manipulate. These complementary processes of accumulation and reinterpretation unite sound and image in the film.

By manipulating the vocal recording into nearly unintelligible utterances, Miller alters the perception of time’s passage. Digital augmentation allows for an expanded vocabulary, where the song is made faster, slower, and reversed. Fragmented and repetitive, the sound disrupts the notion of a beginning, middle and end—acting, instead, as a pattern which cycles through phrases.

William Kentridge (South African, b. 1955), Zoetrope, Still from The Refusal of Time. © William Kentridge; photo courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery

DANCE

Dance—or movement—is evolving all the time.

—Dada Masilo

Kentridge’s collaboration with dancer and choreographer Dada Masilo began when he first saw her perform, admiring her ability to embrace tradition, all the while destabilizing conventions. Born in 1985 in Soweto, Johannesburg, Dada Masilo began dancing with an all-girl dance group named the Peacemakers at age 11. As a choreographer, she is an innovative, passionate, and expressive storyteller. Her work is narrative, often arising out of reinterpretations of classical ballets, including Romeo and Juliet, Swan Lake, and Giselle. Dynamically reframing old stories, Masilo explores contemporary issues, challenges injustice, and questions expectations.

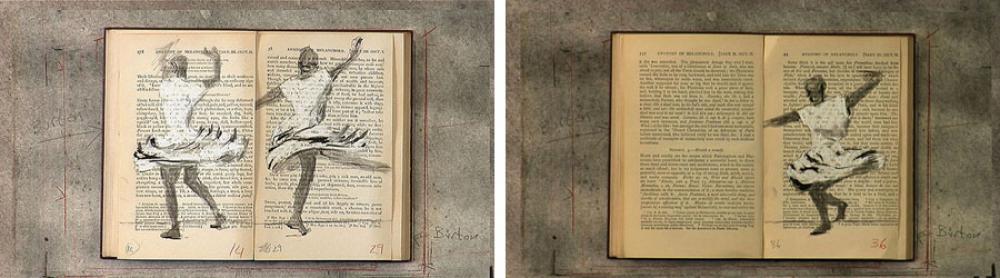

Masilo is interested in the blending of languages, seeking to meld dance styles. Integrating classical ballet, traditional South African Zulu dance, and modern dance, Masilo invites us into a world of movement where techniques are re-contextualized. Masilo recognizes that the way we move is in flux—always changing, historically dependent and intrinsically linked with time. The temporal is deeply affected by the physical: we feel time in—and through—our bodies as we age.

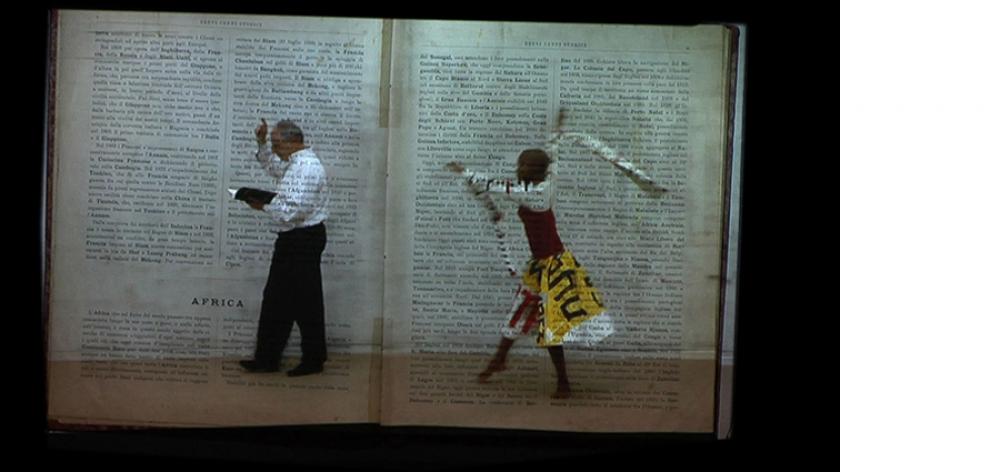

Masilo’s rapturous spinning in Tango for Page Turning reflects time itself, her body comprising a kind of clock. Her hands point directionally while she rotates, as if to indicate the passage of hours. Yet, she spins both forward and in reverse, playing time backwards to deny the imposition of a clock, which can only progress in one direction.

Kentridge and Masilo’s meeting of ideas is perfectly expressed in a climactic moment in Tango for Page Turning. At the beginning of the film, the artist and dancer remain on separate pages of the book; slowly, they move toward each other, until they suddenly collide and vanish.

ART AND SCIENCE

The power of physics lies precisely in its ability to extend a metaphor beyond this or that circumstance.

—Peter Galison

Bridging science and art, Kentridge and Peter Galison, a physicist and historian of science, have worked to form connections that reach beyond the confines of their disciplines. While their fields use different tools and methods, both can provide detached contemplation of abstract ideas and offer reprieve from mundanity.

ABSOLUTE TIME AND RELATIVITY

Time and clocks have a hold on us, both practically and allusively. Shifts in their history disturbed the whole culture.

—Peter Galison

The industrial revolution and its accompanying technologies created a need for standard measurements of weights, lengths, volumes, and even time. Since factories required measured hours for wages, and efficient communication relied on synchronized clocks, time had to be quantified and controlled. These changes, beginning in the late 18th century, introduced a standard notion of time that regulated daily life.

In the 19th century, time became a symbol and manifestation of British colonial control, centralized at the Greenwich Meridian. The time prescribed by newly implemented time-zones disturbed the rhythms of life in some British colonies. Noon in South Africa, for example, no longer occurred when the sun was positioned overhead; the workday came in conflict with a natural experience of time.

William Kentridge (South African, b. 1955), Observatory Room, Still from The Refusal of Time. © William Kentridge; photo courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery

Kentridge and Galison shared stories about these histories. For example, they researched an anarchist named Martial Bourdin who attempted to blow up the Greenwich Meridian in 1894. His act was one of resistance against the authoritarian constraint of industrialized time, in essence a refusal of time.

Kentridge and Galison also examined contemporaneous developments in physics, which conflicted with the absolute time of industrialized society. Einstein’s 1905 theory of relativity grappled with synchronizing clocks to monitor trains at geographically distant stations. He realized that time must be understood relationally: when someone says “the train arrives at 7 o’clock,” they mean that the train pulls into a particular station and a particular clock strikes seven concurrently.

Einstein proved that there is no fixed frame of reference for things in motion, an idea central to Tango for Page Turning. The film considers one body’s relation to another as a form of synchrony. Kentridge twins himself and Dada Masilo, duplicating their drawn figures on either side of the book. Masilo’s two spinning images are nearly synchronized but always in slight disharmony. These displaced mirror images illustrate relativity: they are delayed, just like Einstein’s clocks in distant train stations.

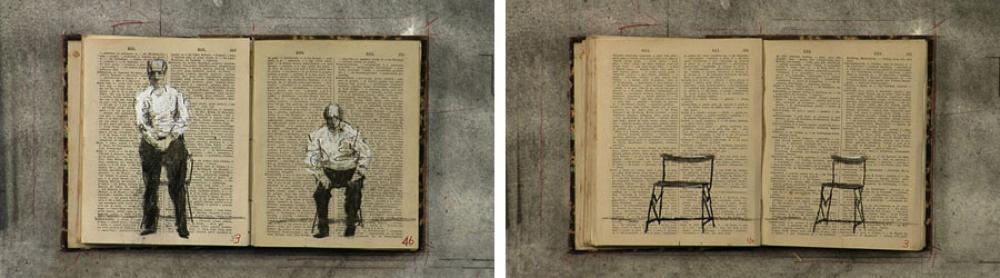

For Kentridge, the mirror image is both an inquiry into time and an exploration of psychological doubling. He believes that individuals experience a fracturing of identity, where they are split into conflicting interests and roles. In Tango for Page Turning, Kentridge’s mirror image is in conflict, as his split-self alternates between sitting and standing.

What is the cost of having many identities with incompatible impulses? We become out of sync with ourselves, our surroundings, and one another. Kentridge and Galison explore what they refer to as “an elastic form of synchronization,” where harmony is found in accepting this complex multiplicity of time and selfhood.

William Kentridge (South African, b. 1955), Observatory Room, Still from The Refusal of Time. © William Kentridge; photo courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery

BLACK HOLES AND STRING THEORY

Is a black hole the end of time?

—William Kentridge

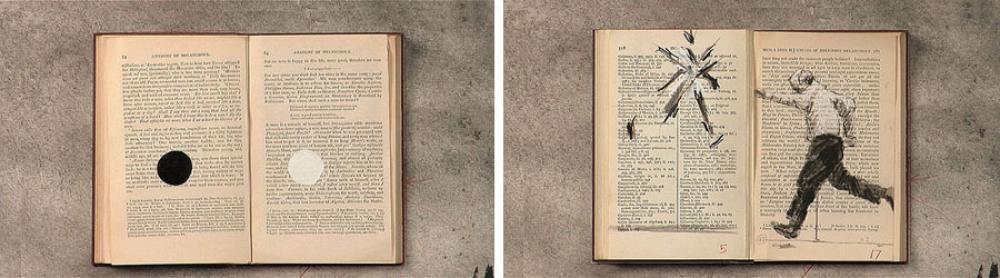

When a large amount of matter becomes compressed into a small area, spacetime seems to rip open, forming a black hole. What lies beyond the mouth of a black hole remains unclear. Debates regarding black holes question what happens to information and matter when it passes through: does it disappear forever—or is it somehow preserved?

In an interview, Galison explained that some string theorists believe information is not annihilated when it falls into a Black Hole. Instead, “all of the information that falls into that hole would leave something on the surface—a kind of holographic image of the thing that had fallen into it. If that is so, then some trace of memory remains.” Kentridge uses this idea as a metaphor, asking what is left of us after we are gone. Death and black holes present the same uncertainty. What happens after we cross these thresholds remains elusive. Using an old dictionary and repurposing images and song, Kentridge explores how information is never lost, though it may become chopped and rearranged.

This eternalized archive captures memory. If information cannot be lost, then nothing can truly be forgotten, yet there are moments that we would rather take back. In Tango for Page Turning these ideas materialize as the words undo, unsave, unsay, unremember, which appear across the pages. Kentridge reminds us that while we cannot rewind time, we can work to reassess—rather than deny—history. In Tango for Page Turning, art-making becomes a retributive meditation on memory.

EMBODIED TIME

Individuals carry with them a subjective experience of time, measuring personal moments in their motions. In Give Us Back our Sun, a transcribed conversation between Kentridge and Galison, Kentridge explains that “when the sun in the heavens is directly overhead, that is the time we call noon. We take our time from the stars and bring it down to the scale where it is incorporated into individual bodies, where your heart, lungs and pulse turn the body into a kind of human clock, a breathing clock”. The great scientist and philosopher Galileo used his own body for measurement, counting his heartbeats to quantify time when conducting experiments. This understanding opposes an experience of time divided into 24 hours, each containing 60 minutes. Instead, time exists on a macrocosmic level of planetary motion, and is experienced at our own pace, quantified in breath and regulated by our somatic experience, emotions and thoughts.

Time operates on many scales: the cosmic influences human experience, which is made up of atomic and subatomic activity. In Tango for Page Turning, we sense all of these experiences occurring simultaneously—lines and brushstrokes suggest the movement of miniscule atoms or expansive galaxies. Abstraction and figuration coalesce showing time in footsteps and moving globes. Measuring like this reflects daily experience— where some moments seem to stretch out infinitely, other weeks can pass quickly, and even years, seen in hindsight, can condense into mere seconds.

Kentridge inquires into our experience of time, showing that it can be elastic. This collaborative meditation on time directs our own experience of it—for however many breaths we watch.

—Sylvie Mayer, 2017 Institute for Curatorial Practice Intern

Works Cited

Fraser, J. T., and Nathaniel Morris Lawrence. The Study of Time II. Springer-Verlag, 2012.

Galison, Peter. Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps: Empires of Time. New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 2007.

Galison, Peter, et al. William Kentridge: the Refusal of Time. Paris, Ed. Xavier Barral, 2013.

Kentridge, William, et al. William Kentridge. Edited by Rosalind Krauss, vol. 21, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2017.

Events And Links

Tango for Page Turning

South African artist William Kentridge (b. 1955) is internationally-recognized for his film, drawing, sculpture, animation, and performance. For more than three decades, his work has explored contentious political systems such as colonialism, totalitarianism, and apartheid through powerful...

Donald Weber, Lucia, Ruth and Elizabeth MacGregor Professor of English, Mount Holyoke College

Give

Give