August 11, 2011

What are the questions facing the socially concerned photographer today? What would an exhibition of present-day documentary photography, aware of its own historical past and conscious of current social issues, look like now? What new strategies are there to address the obstacles and opportunities created by rapid media changes and intensified cross-cultural contact?

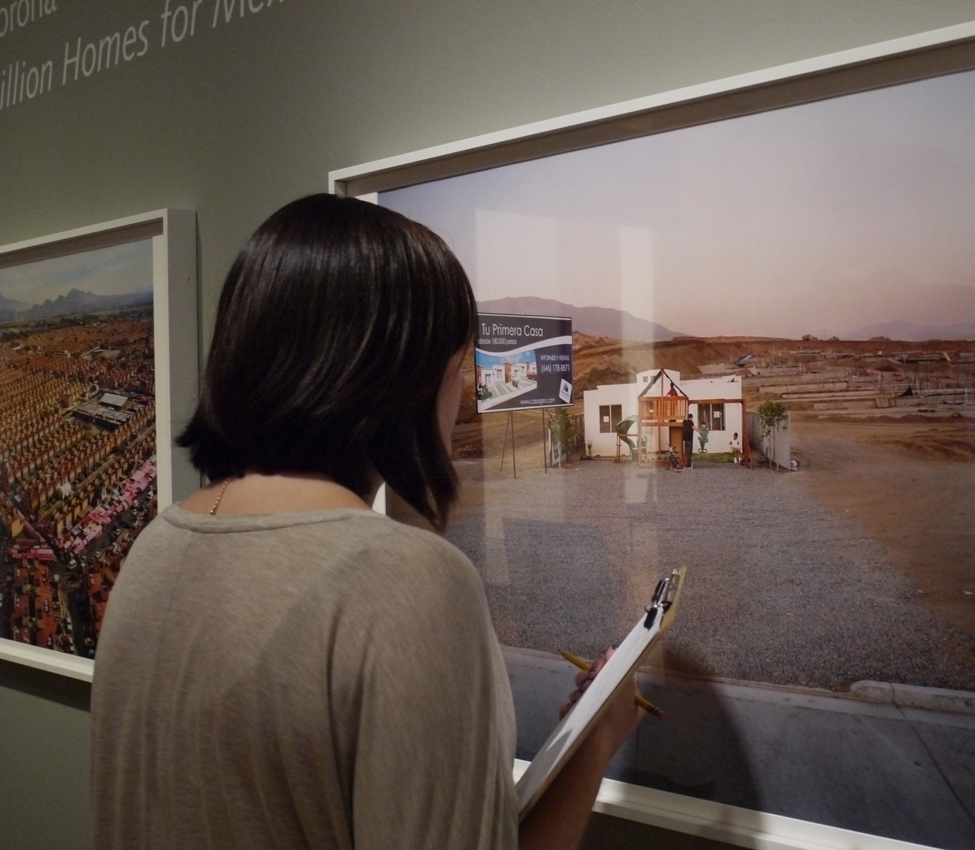

In answer to these questions, the exhibition, World Documents, on view at Mount Holyoke College Art Museum this fall brings together the work and the ideas of important and eloquent contemporary photographers who represent different generations and are concerned with different parts of the world. These photographers understand the role of the camera and photographic technology in strikingly varied and often competing ways. Confronted by the social and cultural changes wrought by immigration and migration, post-colonialism, ethnic nationalism, and global conflict, and also conscious of the social and activist legacy of documentary photography, they each put forward new goals and distinct styles for the photographic document. The exhibition is curated by art historian, critic, and photographer Anthony W. Lee, Professor of Art History at Mount Holyoke College.

The complexity of documentary photography has emerged in stages over the past century. While it originated in campaigns for social and political reform in the Progressive Era, today it has become clear that the celebrated early documentary form was bound to its place and time. Nationalistic, bestowing faith on the authenticity and veracity of camera work, and bearing witness to trauma in an advanced industrial society, it addressed a specific American context.

Following the 1950s, documentary photography evolved as a modernist “artistic” practice, facilitated through the success of exhibitions such as New Documents, mounted at The Museum of Modern Art in 1967. Photographers like Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand created images in stark contrast to those from an earlier generation of photographers, directing the documentary approach toward more subjective ends. Seen as a form of expression as potent and meaningful as any work of art, the photographic ambition was, in the words of MOMA’s curator of photography John Szarkowski, “not to reform life, but to know it.” Over time, this approach gained favor with critics, curators, and collectors.

But what now?

World Documents presents the work of some of the most compelling photographers on the current scene, juxtaposing their disparate ideas of documentary photography and familiarizing audiences with social issues facing different peoples of the world. Although some possess long distinguished oeuvres, while others are at mid-career, and still others are just emerging, they share a commitment to photography’s social, ethical, and moral possibilities; they are attentive to the ebb and flow of social and political relationships on a worldwide scale; and they are mindful of the camera as a producer of meanings, not merely a passive recorder or witness of events. The exhibition presents notable or signature projects undertaken by the photographers in order to suggest what a documentary project can be like in an individual photographer’s hands, while also

permitting comparisons within and between the projects.

The photographers tackle key issues across the globe. Livia Corona focuses on new housing developments in Mexico; Binh Danh grapples with the history of torture and violence in Cambodia; Jason Francisco meditates on the condition of American Jews living in the diaspora; Julia Komissaroff documents the dramas for Palestinians living in conflict-scarred Jerusalem; Pok Chi Lau explores the legacy of the Cultural Revolution in post-Tiananmen China; Ken Light documents the plight of child laborers in India; Paul Weinberg investigates the persistence of older forms of spiritualism in post-apartheid South Africa; and Ouyang Xingkai follows the fortunes of the people living in a once bustling but increasingly withering river town in central China.

A full-color catalogue accompanies the exhibition and includes statements about the individual projects by each of the photographers and an introductory essay by Anthony Lee.

Admission to World Documents and other exhibitions is free; donations are welcome. The Museum is open Tuesday-Friday, 11 a.m.-5 p.m. and Saturday/Sunday, 1-5 p.m., and is fully accessible. Parking is available nearby.

The Mount Holyoke College Art Museum in South Hadley is a leading collegiate art museum. Its comprehensive permanent collection of 16,000 objects features Asian art, 19th- and 20th century European and American paintings and sculpture, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman art, Medieval sculpture, early Italian Renaissance paintings, and an extensive collection of works on paper. For more information, visit www.mtholyoke.edu/artmuseum or call 413-538-2085.

Electronic images are available upon request.

GIVE

GIVE