Keeping Track of the Past: Exhibition Files and Museum Records

Curatorial Intern Lydia Holleck ’25 shares her experience working on a project to digitize the Museum’s exhibition records, ensuring that information from every exhibition dating 1931–2025 is accessible for Museum staff in the online database. In particular, she reflects on one exhibition, “Transformations in Hellenistic Art,” that stood out to her.

Before beginning my Curatorial internship at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, I hadn’t thought much about how exhibitions are documented and preserved. While I knew museums kept records of each artist and object, I had never considered the meticulous record-keeping required to track each exhibition’s history. That all changed when I began working on a project in the Museum’s record room.

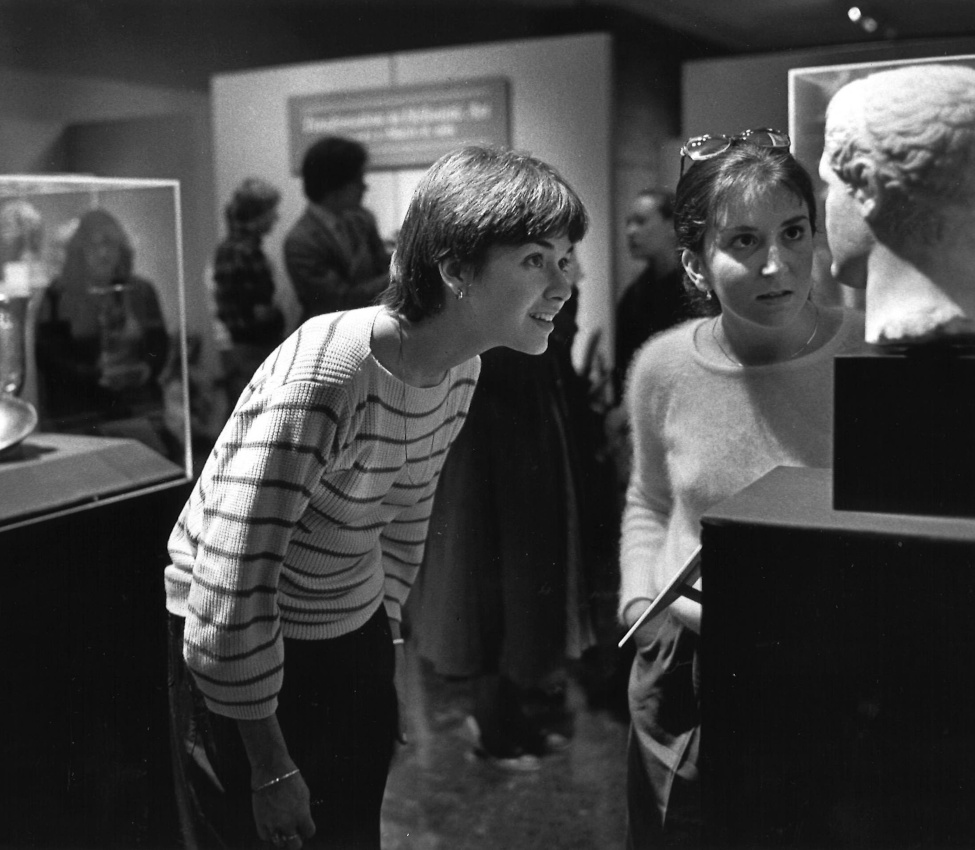

Emily Wood

Lydia Holleck ’25 works on cataloging the exhibition files.

For this project, I was assisting with the digitization of the museum’s exhibition records, working to ensure that information from every exhibition since 1931 is accessible for Museum staff in an online database. The Museum holds paper copies of these records in organized filing cabinets, and my role involves reviewing, organizing, and entering key details into the digital system. This work has opened my eyes to the importance of exhibition files in preserving a museum’s history and shaping future curatorial decisions.

What Are Exhibition Files?

Exhibition files serve as a museum’s record of what has been displayed in temporary exhibitions, showing the development of an exhibition from initial thoughts and planning to the final installation. These files document past and present exhibitions, including essential details such as titles and dates; featured artworks and artists; curatorial statements and exhibition design plans; invitations to gallery openings and events; correspondence between museum staff, scholars, and other institutions; and photographs of the exhibitions and installations. By maintaining exhibition files, museums can track their exhibition history and ensure that future curators and researchers have access to information about previous exhibitions and programming.

Although the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum was established in 1876, exhibition records only date back to 1931. This is due to several factors, including the Museum’s early administration, its previous location in Dwight Hall, and changes in record-keeping practices over time. Until 1970, the Museum was run by the Art History department. When the leadership of the Museum was transferred to a professional museum staff in 1970, record-keeping became more systematic. This is one of the shifts in organization that I noticed as I worked through the exhibition files.

My Observations

Over the years, the content of exhibition files has evolved significantly. While each file contains core details such as exhibition dates, older files could be sparse, sometimes containing very limited information on multiple exhibitions in a single folder. In contrast and reflecting developments in museum practices, more recent files are very detailed, often requiring multiple folders to accommodate extensive documentation, correspondence, and photographs.

Prior to the formal creation of the Museum’s Teaching with Art Program in 2009, the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum historically hosted multiple exhibitions each academic year; sometimes as many as three in the fall semester and three in the spring. I also learned that the Museum used to remain open during the summer, with exhibitions ending or opening in July. Today, however, the Museum closes after Reunions in late May and remains closed until classes begin again in September. During this time, staff are able to focus on behind-the-scenes tasks, including gallery reinstallation.

Archival Photograph of Exhibition Installation in 1983

Examining older files has also revealed shifts in how exhibitions engage audiences. The Museum’s galleries were renovated in 2001 with the addition of a large temporary exhibition space, influencing how exhibitions were designed and displayed. In earlier decades, galleries typically featured a uniform wall color, and objects were grouped based on cultural or chronological similarities. Nowadays, this approach has evolved. For each exhibition, the Museum refreshes the galleries, changing the wall colors, spatial arrangement, and the thematic connections between objects.

The way objects are presented has also evolved. I noticed that in many past exhibitions, the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum often grouped similar objects together, such as sculptures from the same culture, reinforcing traditional categorizations. Today, the Museum is increasingly juxtaposing objects from different cultures and time periods to encourage new interpretations. The RELAUNCH LABORATORY exhibition (on view September 3, 2024 – May 25, 2025) exemplifies this shift, focusing on innovative object pairings that challenge conventional categorizations.

Another trend I noticed was the prevalence of traveling exhibitions. These shows circulated among multiple museums, often with standardized object groupings and labels. This practice fostered a sense of collective museum engagement, as institutions presented exhibitions and similarly allowed for loans of artworks that museums didn’t have in their collections. Over time, Mount Holyoke College has moved away from this approach, opting towards curating exhibitions based on the Museum’s own permanent collection. However, the Museum still sends loans to and receives loans from other institutions.

“Transformations in Hellenistic Art”

Petegorsky/Gipe - VIEW OBJECT DETAILS

While Head of a Woman was the motivation and focal point for the show, the exhibition also included Hellenistic objects borrowed from seventeen institutions and private collections, ranging from college art museums to larger institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition files for Transformations in Hellenistic Art are extensive, consisting of eight folders that document every stage of planning and execution. The first two folders provide an overview of the exhibition’s development, including original correspondence with museums and collectors regarding potential loans. These folders contain loan agreements, insurance details, records of objects that were ultimately not included, invitation lists for lending institutions, and security forms.

Beyond these logistical documents, several folders focus on object condition reports and receipts, ensuring the safe handling and tracking of each object. Other folders detail the exhibition catalogue planning process, including correspondence about cover design, selected texts, and object descriptions. Public relations materials, along with a full catalogue of photographs taken before the objects were displayed, also form part of the archive. One of the most fascinating files, in my opinion, contains photographs of the exhibition itself, capturing visitor reaction and providing a visual record of how the objects were displayed and arranged on pedestals and in glass cases.

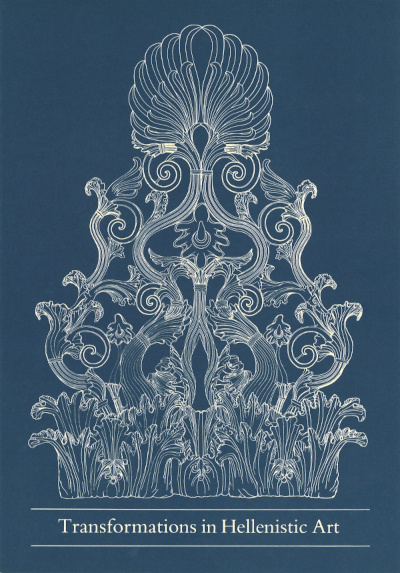

Cover of Transformations in Hellenistic Art Exhibition Catalog

The objects on view in this exhibition varied in material, subject matter, and scale, but included statues, figurines, sculpted heads, and reliefs. These works were crafted from diverse materials such as silver, terracotta, various types of marble, limestone, and bronze, reflecting the range and sophistication of Hellenistic artistry.

Together, these archival materials offer a comprehensive record of how Transformations in Hellenistic Art was put together, organized, and received, preserving a snapshot of the Museum and the object’s curatorial history.

Closing Reflections

While taking on this project may sound like a redundant task, going through the files gave me insights into past exhibitions and museum practices. I appreciated learning about the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum’s history and historic exhibition themes. Furthermore, I loved seeing photographs of previous exhibitions, noting the changes in display and labeling methods, and even the different layout of the galleries. Additionally, it was fascinating to see when the Museum accessioned various works of art, including ones that are on display today, and how they were inaugurally displayed. I’m so grateful for this opportunity to explore the Museum’s historic exhibitions.

Overall, this cataloging project has taught me the importance of record-keeping. I have come to appreciate the crucial role of record-keeping in museum work. Exhibition files serve as an institution’s history, and also inform future curatorial decisions, research, and scholarship. As museums continue to evolve, the careful documentation of exhibitions ensures that past insights remain accessible for generations to come.

Give

Give