Tango for Page Turning: Related Words

Self-guided tour, one of MHCAM Journeys, developed for visitors in Summer 2017

William Kentridge’s 1-channel projection Tango for Page Turning explores the complexity of time. Charcoal drawings, typed text, and spilled ink are collaged on top of an old book as time passes through its turning pages. The work takes inspiration from dance, physics, and the political history of time-keeping, as explored in the online exhibition guide.

After reading the guide, you might wonder if similar ideas appear in other works from the Museum’s collection. This tour contextualizes Kentridge’s film within the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, creating a network of related objects on view. The works represented here explore similar concepts as Tango for Page Turning, including meditations on our experience of time, an artifact of the industrial revolution, and photographs which illustrate laws of motion.

1.

![Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919), Danseuse au Tambourin [Dancer with Tambourine], ca. 1918-19 model Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919), Danseuse au Tambourin [Dancer with Tambourine], ca. 1918-19 model](/sites/default/files/styles/test/public/mh_1997_9_1_v1-cdm.jpg?itok=hnoLL6Aq)

Pierre Auguste Renoir (French 1841-1919), Danseuse au Tambourin [Dancer with Tambourine], ca. 1918-19 model, Bronze, Gift of Mrs. Harold Kaplan in honor of her daughter Irene Kaplan Leiwant (Class of 1947)

Whether translated into film, like in Tango for Page Turning, or fixed in a painting or sculpture, dance has a long history in the visual arts. In this bronze relief by Renoir, a dancer with a tambourine is frozen in time between movements. Though she remains still, one of her arms protrudes from the relief, creating an illusion of gesture and motion.

2.

![Zao Wou-Ki (French, b. China, 1920-2013), Paysage au soleil [Sunny Landscape], 1950 Zao Wou-Ki (French, b. China, 1920-2013), Paysage au soleil [Sunny Landscape], 1950](/sites/default/files/styles/test/public/mh_1953_1_j_rii_v1-cdm.jpg?itok=upU4nRnN)

Zao Wou-Ki (French, b. China 1921-2013), Paysage au soleil [Sunny Landscape], 1950, Color etching and drypoint, Purchase with the Nancy Everett Dwight Fund

In this intimately sized print, deeply etched lines form rhythmic trees that populate the foreground. An uneven circle represents a massive sun, which presides over the horizonless landscape. The paper is subtly tinted a pale blue green, and vignetted by smudged ink. Time is tangibly expressed in the landscape. Rings within tree trunks show their age and the sun provides a day-night cycle as we rotate around its axis. William Kentridge explores how each individual experiences time at their own pace, using information from sensory experience, including sunlight. In this print, the sun is made ever present – overseeing the scene below.

3.

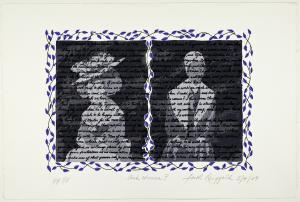

Faith Ringgold (American b. 1930), And Women?, 2009, Serigraph; ink on Rives BFK White, Gift of the Mount Holyoke College Printmaking Workshop

Like Kentridge, Faith Ringgold engages in reframing archival material to question and redirect past histories of exploitation, slavery, colonialism, and inequality. Taking historical imagery and text, artist and activist Faith Ringgold recaptures two important 18th-century women. Surrounded by a blue floral frame, the left side contains a portrait of Abigail Adams, overlaid with a letter to her husband which asks him to “remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors”. On the right side, a portrait of Sojourner Truth is layered with text from her speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” which concludes “these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again”. Ringgold and Kentridge layer text and image, bringing visual and written forms of communication into conversation.

4.

James Watt (British; Scottish 1736-1819), Model of Watt’s Steam Engine, late 19th or early 20th century, Iron and paint, Joseph Allen Skinner Museum, Mount Holyoke College

Peter Galison, a physicist, science historian, and collaborator of William Kentridge is interested in how scientific principles are embodied in technology. An example of this kind of ’embodied technology’ can be seen in this small model of James Watt’s steam engine. Watt applied concepts of combustion and atmospheric pressure in order to develop an engine which was more effective and less costly than any previous conception. This efficient and widely applicable steam engine was invented in the late 18th century. It was essential to the onset of train travel, creating locomotives which would catalyze the industrial revolution. This model, made at least a century after Watt’s initial invention, was used for educational purposes to demonstrate how the steam engine functions.

5.

Berenice Abbott (American 1898-1991), The Science Pictures: Cycloid, 1982, Gelatin silver print photograph, Gift of Joseph R. and Ruth Lasser (Ruth H. Pollak, Class of 1947)

Berenice Abbott visualizes physical phenomena in simple and precise, high-contrast photographs. Illuminating the abstract and usually imperceptible laws of motion with multiple-exposure photography, Abbott shows us how balls roll, move, and collide. For Abbott, photography provided a facile and useful way to translate intangible scientific principles into easily understandable images. While William Kentridge engages with science by extracting metaphors, Abbott’s photographs aim to illustrate reality, showing physics at work.

6.

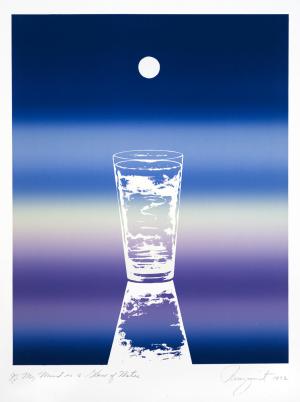

James Rosenquist (American 1933-2017), My Mind is a Glass of Water, 1972, Color lithograph on white wove paper; edition 38/125, Gift of Susan B. Matheson (Class of 1968)

A soft gradient containing vertical bars of deep purple, cerulean blue, and yellow-green forms a background without a definite horizon line. These colors, which undulate to create an illusion of movement, evoke calm contemplation. A white circle is centered in the upper part of the composition indicating the moon. A glass of water and its reflection sit in the foreground, providing humor against the pensive backdrop. One can almost imagine the circle slowly descending into the glass of water, as time passes and the sun rises. Rosenquist’s meditation on time can be understood parallel to Kentridge’s – since we each experience time on our own accord, each artist expresses its passage personally.

Give

Give