Re-Examining Shakespeare's Othello: An Artistic Collaboration

In fall 2018, students enrolled in Associate Professor of English Amy Rodgers’ “Activist Shakespeare” class had the opportunity to work with Curlee Raven Holton’s Othello Re-Imagined in Sepia print series, exhibited at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum. Students engaged with real-world examples of the activism-oriented Shakespeare adaptations discussed in their class.

Introduction

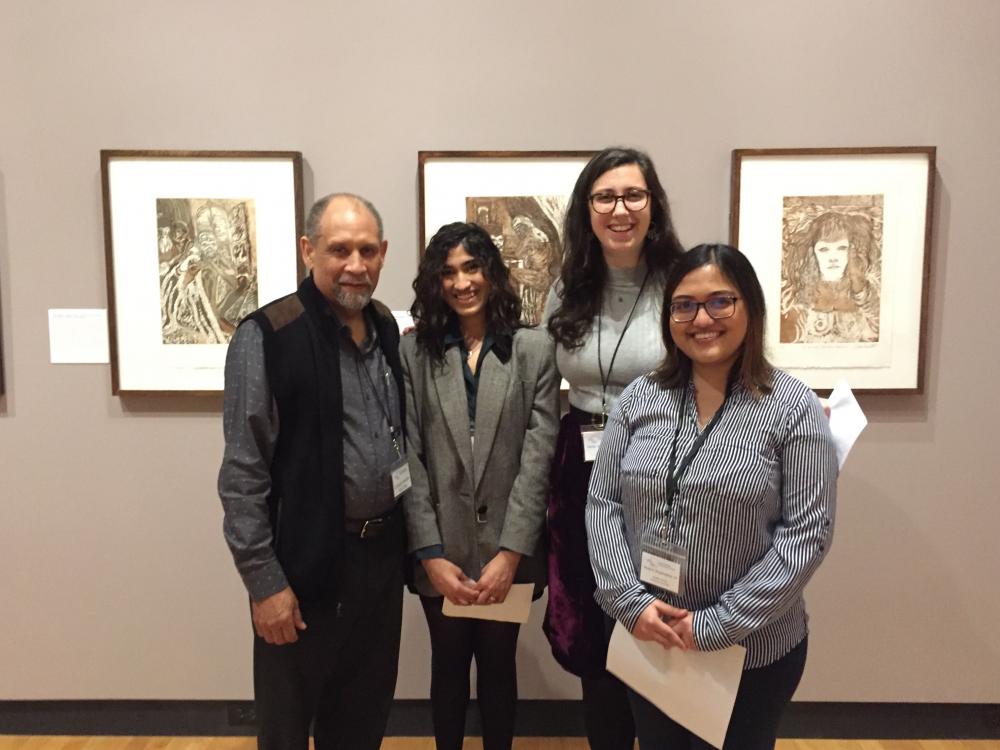

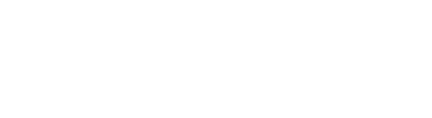

As an assignment for Associate Professor of English Amy Rodgers’s “Activist Shakespeare” class in fall 2018, students collaborated in small groups to write interpretive labels for each of the ten etchings in the Othello Re-Imagined in Sepia print series. These labels were then displayed in conjunction with the artwork in the exhibition. In addition, students had the chance to meet Curlee Raven Holton in person as well as attend a performance of Keith Hamilton Cobb’s critically-acclaimed one-man show American Moor in Rooke Theater. Here Siddhi Shah ’19, Mollie Wohlforth ’19, and Prokriti Shyamolima ’19 each reflect on three different aspects of their experience and share perspectives from their fellow classmates.

I. Making meaning in 130 words or less: writing labels for Othello Re-Imagined in Sepia

Laura Shea

"Activist Shakespeare" students working in the galleries

My other classmates reflected on the label writing process as well:

This experience working directly with the prints was tremendously useful in alleviating my preconceived challenges of the assignment. While the brevity and precision demanded by the label guidelines were difficult, I felt more confident in my ability to synthesize what I saw in the print and its relation to the text.

—Savannah Romeo '19

The most rewarding moment of the process for me was when Curlee Raven Holton visited the exhibition and said that our labels challenged him to see new meaning within his own work. It was very powerful for me to see how his work was interpreted in many ways both by my classmates and by the artist himself based on their experiences.

—Julia Blomberg '19

Writing the label was a different kind of close reading for me. Instead of looking at a particular passage in the book, I was staring at an image and pushing myself to come up with words on a notepad. The writing process almost felt like a meditation practice, as I positioned myself close to the image trying to imagine what Holton would say if he were standing right next to me.

—Jenny Ye '19

II. New ways of seeing: Curlee Raven Holton and Keith Hamilton Cobb's artistic reinterpretations of Shakespeare in the 21st century

Laura Shea

Installation view of Othello Re-Imagined in Sepia, July 2018

Here are two of my classmates’ reflections:

Images sometimes are more powerful than words because they provoke our sense of sight to easily let us picture a scene, directing us to a point that we might have previously ignored when reading the play. For example, when I saw Dreams of Two Different Worlds for the first time, the message that the print signaled was as clear as its title: two worlds, one love and one tragedy. However, after reading the interview and Holton's explanation that this print emphasizes what Othello and Desdemona have given up and compromised for their love, I started to notice the vulnerability of the two characters. Therefore, engaging in other forms of adaptations encouraged me to go back to the original work, seeking evidence to consolidate an argument that later activists are trying to make. Such a complement of Shakespeare's plays and adaptations allowed me to understand literature with a more diverse perspective.

—Alice Ji '21

The idea of having to analyze a seemingly abstract piece of art while combining my ideas with those of a partner seemed daunting to me. It has always been difficult for me to interpret art so I spent a large amount of time with the print To Live Without the Mask of the Past admiring the details and trying to interpret them through Shakespeare’s text. What finally helped me to understand the symbolism behind the piece was reading interviews with the artist Curlee Raven Holton in which he discussed his perspective on the play Othello and what the symbolism of the mask meant to him. I decided to include a quote from him in my label because I felt that it contributed to a broader understanding of not only the piece that I was working on but the themes of his entire collection. Once I understood the meaning behind the piece, it became a pleasure to work with and to write about.

—Julia Blomberg '21

III. Reflecting on our experience: personal perspectives on a complex character

Laura Shea

Students collaborating on label texts

Below are insights from my peers about this experience:

Othello to me was just a normal character like the ones in any other plays, with lots of intricate lines to understand and interpret. However, after taking part in the label writing assignment and watching American Moor, I developed a better understanding of his character, who sometimes struggles with confusion and frustration in the conflicts between race and religion. Therefore, his struggle is between two cultural identities, which might be experienced by many people in their daily lives, not only by Othello. Now we understand Othello not because he is a protagonist in a famous play worthy to be read, but because he is a person like any of us.

—Wenshu Qiao '20

Reading Othello at the beginning of the semester I felt convinced in my perception of Iago as the true protagonist of the play. He often shares his ideas and plans directly with the reader, and much of the plot is forwarded by his ploys. However, by claiming him to be the main focus one greatly risks overlooking the significance and importance of Othello himself. Othello is such a nuanced character who has to endure discrimination from his peers for being a Moor, while simultaneously working hard to establish himself as a part of Venetian society. Unlike Iago, we often do not hear Othello's thoughts directly, but his actions show the great nuance of his character. For example, Desdemona seems to be one of the few people who supports Othello for who he is simply because she cares for him. It seems like she is the closest thing he has to stability and compassion in his turmoil, and yet he ultimately kills her because his mind and will are so thoroughly manipulated and broken by Iago. This concept alone is something that compelled me to consider the immense complexity in Othello as the protagonist.

—Hanna Schoenbaum '21

I read Othello in my senior year English class in high school, so I was already fairly familiar with the play. I admit that I was a bit disappointed, since I took this class in part because I wanted to learn about a broader set of Shakespeare’s plays than I had learned about in high school (tragedies, tragedies, Twelfth Night, and more tragedies!). I found the label assignment to be a fantastic antidote to my complacent attitude. In high school, our analysis had mostly focused on Iago. Carefully studying the symbolism of the print I was assigned helped me gain a newfound appreciation for the nuances of Othello’s character. Despite his efforts to integrate into Venetian society, Othello is a perpetual outsider; other characters, and eventually the play itself, condemn him. The prints tease out Othello’s complexity, while simultaneously showing the immense racism of Shakespeare’s original play.

—Anne Clinton '19

Ellen Alvord

Curlee Raven Holton with Siddhi Shah '19, Mollie Wohlforth '19, and Prokriti Shyamolima '19

Give

Give