Methoughts the Shilling: Teaching History with Money

Money doesn’t just talk. It’s also good to think with. Assistant Professor of History Desmond Fitz-Gibbon describes some of the intriguing stories told by coins and other money-related objects in the MHCAM collection: a Spanish real with layers of history, a gold solidus with a disturbing omission, and an assignat, France’s first paper currency. Taught bienially in the spring semester, Professor Fitz-Gibbon’s History of Money course explores the meaning of money from the distant past to the present day.

Methoughts the Shilling: Teaching History with Money

Professor Desmond Fitz-Gibbon and students in the History of Money course examine money-related objects at MHCAM.

Methoughts the Shilling that lay upon the Table reared it self upon its Edge, and turning the Face towards me, opened its Mouth, and in a soft Silver Sound gave me the following Account of his Life and Adventures.

Professor Desmond Fitz-Gibbon and students in the History of Money course examine money-related objects at MHCAM.

--Joseph Addison, “The History of a Shilling,” (1710)

Joseph Addison’s dream of a talking shilling reminds us that there was a time—easily forgotten in our age of ubiquitous, but disappointingly inanimate currency—when money was very much alive. The silver coin that haunted his sleep told him of its birth in the mines of colonial South America, its minting as a shiny new Elizabethan shilling, and its subsequent journey through decades of the seventeenth-century, passed from “Hand to Hand,” between soldiers, a brewer, a butcher, a preacher, a thief, a miser and a gambler. Living money offered a metaphor through which one could trace the outlines of a new commercial society. To riff on the anthropology of Claude Lévi-Strauss, you could say that Addison showed how money is “good to think with.”

Modern economics tends to think of money as something functional and transparent, a unit of account, a store of value, or a means of exchange. It greases the wheels of commerce, but nothing more. As material history, however, money is inscribed with the human relationships that make it such an effective social tool for ordering exchange, power and authority. It is not for nothing that rulers of all sorts have sought to mark coins and notes with their own images or threatened death to those who would challenge their authority to coin. Nor is it always the case that money tells a single or coherent story of authority and rule. Sometimes money talks with more than one voice.

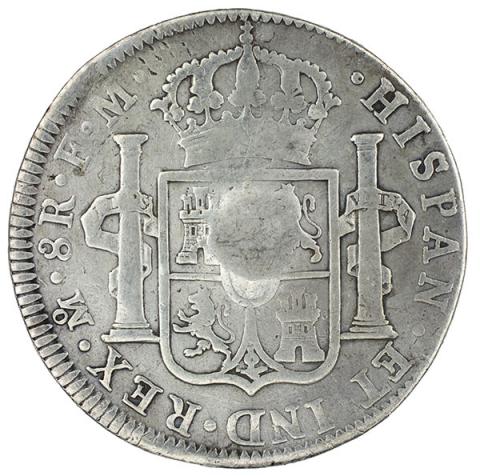

Take, for example, this counter-stamped Spanish eight-real, which also contains some finely etched graffiti issuing from the mouth of King Carlos IV and celebrating the “11th of May, 1797.” Talking money indeed!

Carlos IV (minted under); George III (minted under); Unknown (engraver), Spanish; British, 8 reales of Charles IV with George III countermark, 1796-1820, Silver (AR); milled and engraved, 1 9/16 in, Purchase with the Marian Hayes (Class of 1925) Art Purchase Fund, 2013.16

The counter-stamp, impressed on the neck of Carlos, is of the British King, George III. One coin, three different histories. First, a coin minted—like Addison’s shilling—in the New World, but circulating throughout Europe, the Middle-East, and Asia as one of the world’s first global currencies. Second, the bust of George III records the great crisis of 1797, when, in the midst of the French Revolution, the Bank of England suspended payments on its banknotes and drove the government to all sorts of expediencies, including the issue of captured Spanish bullion as stand-in British change. And what of the graffiti? What was worth celebrating on the 11th of May? A great political event? A famous battle? A romantic engagement? A mystery still, but also a reminder that money has many uses, not all of them economic.

Thinking with money—and listening to the stories it can tell about life in different times and places—is what first inspired me to design a course in collaboration with the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum and its rich collections of money-related objects. The opportunity to tell a larger story of money across thousands of years and using dozens of objects was both intimidating and exciting. Fortunately, Mount Holyoke has a collection that is more than up to the task. Through workshops designed to explore and analyze the information contained in these artifacts, students connect material history to theoretical and historical questions about the origin, uses and meaning of money in past societies and cultures. This is history that Addison surely would have enjoyed!

-Desmond Fitz-Gibbon, Assistant Professor of History

Sumerian clay tablet

Sumerian clay tablet

We begin the course with the origin of money, which remains an obscure and deeply contested question. This clay cuneiform tablet from the ancient city-states of Sumer records the payment of rations and reveals some of the social technologies—like numeracy, literacy and accounting—that were crucial to money’s early conceptual development. Studying objects like this one challenges prevailing assumptions about the lack of abstraction in pre-modern money or the relative importance of coined currency over other forms that money can take.

Mesopotamian; Babylonian; Sumerian, Tablet with cuneiform inscription documenting the payment of rations of beer, bread, garlic, oil, and spices to several individuals, ca. 2310 BCE (Ur III, Shu-Sin, year 5, month 6), Clay, 1 1/8 x 1 1/16 x 7/16 in, Gift of Mrs. Allen E. Baker (Alison Ostrander, Class of 1936), 1976.5.2.

Solidus of Irene

Images on money very often reveal histories of political authority and the communication of power. This coin, a gold solidus, conveys a very clear message, both by what is present in the image and what is not. Present, on both sides of the coin, is a portrait of Irene of Athens, empress and sole ruler of the Byzantine empire. Missing is her son, Constantine VI, whose image had appeared alongside hers on coins minted up to 797, the year she had him killed and his eyes gouged out.

Irene of Athens (minted under), Byzantine, Solidus of Irene, sole reign, 797-802 CE, Gold (AV), 3/4 in, Purchase with the Marian Hayes Art Museum Fund, 2012.27

Denier of Louis I

We owe the modern penny (or pence, or pfennig) and its related denominations of shillings and pounds to the Franks, and in particular to their most famous king, Charlemagne, who standardized the use of silver currency throughout his empire. This coin was minted under his son, Louis the Pious.

Louis I (minted under), Carolingian; Frankish; French, Denier of Louis I, 814-840 CE, Silver (AR), 13/16 in, Gift of the Estate of Nathan Whitman, 2004.13.524.

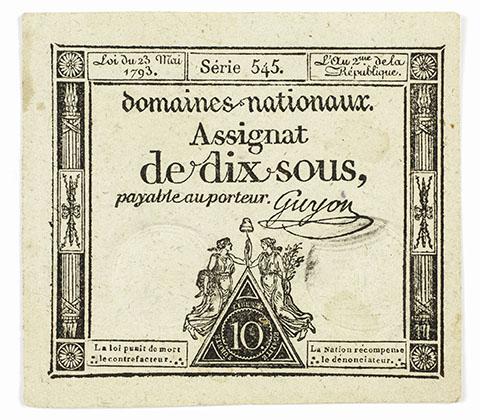

French Revolutionary Assignat

A major theme in this course is the history of trust, and its importance in securing the legitimacy of money as a social institution. During the French Revolution, the government issued France’s first paper currency, the assignat, seen here in an example from 1793. Despite repeated efforts to build trust in these notes—through words and images associated with the ideals of liberty and justice—the political crises of the Revolution ultimately undermined the assignat’s success.

French, Assignat, 1793, Paper with ink, Gift of Aaron F. Miller in Honor of Ellen M. Alvord (Class of 1989), 2017.2

Give

Give