Lotus Shoes: The Stories of Chinese Women and American Women Missionaries

The Almara History in Museums and Stomberg Curatorial intern Keyang Zhao ’25 explores the history of footbinding and missionaries in China by looking into lotus shoes at the art museum.

In January 2024, I took on an internship through the history department at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum. My main goal was to look into objects in the museum’s collections donated by Mount Holyoke missionaries who went to China. In the 19th century, during Mount Holyoke’s days as a seminary for women, Christianity was embedded in the institution, and missionary work was a frequent next step for graduates. The missionaries often acquired objects during their time abroad and sent them back to the seminary. This eventually formed the College’s “missionary collection,” which is now part of the Museum’s collection. I became interested in studying material culture related to this history through my Fall 2023 Independent Study research. My project was on the experiences of Chinese women students of higher educational institutions in the US and I learned that most of the earlier generations of students were connected to missionaries. In some cases, the Chinese women were directly inspired and enabled by missionaries to pursue a higher education abroad. I plan on continuing this research in the future, so the J-term internship was a great opportunity for me to learn about an earlier part of this history and establish foundational knowledge. Going into this internship, I did not know what to expect but was curious to find out more about the types of objects that missionaries deemed important enough to send to Mount Holyoke.

Seeing the Shoes

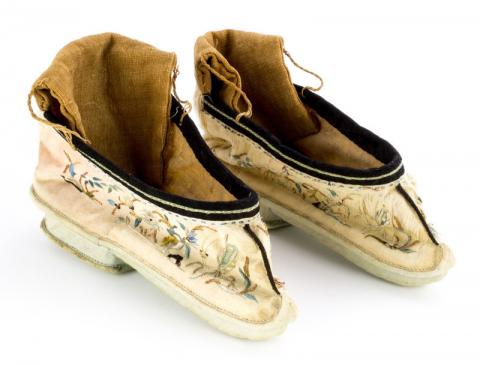

Looking through the MHCAM database for items that fit the description, I realized that there were a lot of shoes in this set of objects, all of which date to the late 19th century (Qing dynasty). When the Museum staff brought the shoes out of storage so that I could see them in person, I was struck by their size; they only measured about three inches in length, which was a stark contrast to the shoes I see and wear in everyday life. Some of the shoes, such as the blue ones shown in the image above, were incredibly well-preserved. The blue shoes are attached to a pair of red leggings with green hems that were stuffed and sown at the top to give them the appearance of how they would look being worn by a person. Given their excellent condition, these shoes were probably never worn but instead made to be sold to the missionaries or other foreigners as curiosities.

Laura Shea - VIEW OBJECT DETAILS

History and Practice of Footbinding

These shoes were meant for Chinese women with bound feet. They are named lotus shoes, after the name for bound feet, lotus feet. Seeing these shoes reminded me of the stories my grandmother used to tell me of her grandmother, who had bound feet. My grandmother remembered her as someone who always struggled to walk because her bound feet limited her movements. However, despite her limited mobility, she liked to remain active and would choose to hobble around instead of staying put in one place. For me, the lotus shoes put into perspective her lived experiences.

Laura Shea - VIEW OBJECT DETAILS

The footbinding process was a painful one. To achieve the distinctive lotus-like shape and ensure that the feet remained small, women’s feet were bound with binding cloths at the young age of about five years old.3 After a few years, toes were bent under the sole and the foot arch would be forcibly broken. The footbinding process took place within the women’s quarters of the home and only women were allowed to participate. It was ceremonial and symbolic: it represented a prelude to a woman’s coming-of-age and served as an acknowledgment of her womanhood.4 For the rest of their lives, women with bound feet lived with limited mobility as they were only able to hobble around.5 This specific movement and posture was considered the beauty standard.6

Footbinding Through the Eyes of Missionaries

To find out more about the individual missionaries who gifted the shoes to the Museum, I headed to the College Archives and looked through their files. Most of the Mount Holyoke graduates who went on to become missionaries in China believed that they were doing an act of service to save the “heathen” (non-Christian) people. To accomplish their goals, they followed a general pattern of activity. They would, first, join a mission organized by a church or a Christian organization and travel to China. There, they would spend their first year learning the Chinese language and becoming proficient at it. From their second year onwards, the missionaries would be stationed in a city, where they would usually work as teachers in girl’s schools, or, if they had medical training, as physicians.

Their work also included interacting with local women, often going from house to house, and holding discussions about Christianity with them. Some missionaries advocated for women’s education by encouraging families to send their daughters to school. Some of them also held strong beliefs against footbinding. This became apparent in a letter I read from Edith C. Boynton (class of 1906), who went to Amoy (Xiamen) in 1915 and knew Helen Russell, who gifted the museum the blue lotus shoes with red leggings. In her letter, she described footbinding as one of “China’s greatest evils.”7

Laura Shea - VIEW OBJECT DETAILS

Other missionaries shared the hatred for footbinding and tried to push for an end to the practice through different means with varying levels of success. The anti-footbinding movement only took off with the participation of Kang Youwei, a Chinese scholar and reformer. He set up the Anti-footbinding Society in 1894, which, at the height of its popularity, had more than 10,000 members. Over time, more and more people turned away from the practice. In my family, footbinding ended with my great-great-grandmother. In 1911, footbinding was officially declared illegal by the newly established Republican government.8 This is why none of the lotus shoes in the museum’s collection were made after the early 20th century. Introduced in the year of the successful overthrow of the Qing monarchy and the establishment of China as a republic, the anti-footbinding law symbolized a shift away from tradition to embrace modernity.

Thinking about Footbinding Today

Footbinding was a complicated practice. We should neither gloss over it nor simply accept straightforward explanations. On one hand, the practice was undeniably a tool of patriarchal oppression because women had to physically alter their bodies to adhere to beauty standards. The missionaries certainly understood footbinding in this way and the shoes they sent back to Mount Holyoke served as evidence of this “evil” and foreign practice. On the other hand, the motivations behind foot binding were so much more complex and it would be an oversimplification to see the practice as just a tool of the patriarchy. We must try to understand how the women with bound feet saw this practice and acknowledge that beyond being a sign of their oppression, it was also a way for them to challenge their social status by emulating elite women, protect themselves from outdoor manual labor, and improve their chances of socially advancing through marriage.9 Footbinding, to the Chinese women, was a survival tactic for living under the pre-existing system.

The museum’s collection of lotus shoes gave me the opportunity to dive into the practice of footbinding. My research into the shoes illuminated the ways in which the missionaries experienced and interacted with the material culture they came across, their work, and their relationship with the Chinese communities. Beyond that, this internship allowed me to gain important insights into Chinese and American historical contexts, which will be helpful for my future research. Overall, the shoes, and their presence at the Museum, tell the powerful story of two different groups of women and the instance of their encounter.

Emily Wood.

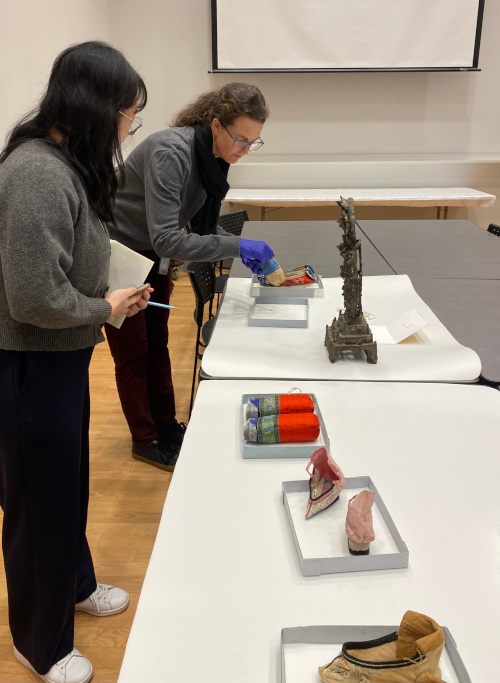

Keyang Zhao '25 and Abigail Hoover, Associate Director of Registration and Collections, examine the shoes.

1 Beverly Jackson, Splendid Slippers: A Thousand Years of an Erotic Tradition (Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 1997), 111.

2 John Robert Shepherd, Footbinding as Fashion: Ethnicity, Labor, and Status in Traditional China (University of Washington Press, 2018), 3, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvcwnt8c.

3 Shepherd, Footbinding as Fashion, 3.

4 Dorothy Ko, Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet (Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press, 2001), 54.

5 Shepherd, Footbinding as Fashion, 3.

6 Jiaqin Zhang and Huie Liang, "Porcelain-made Lotus Shoes in the Qing Dynasty of China," Ceramics, Art and Perception no. 110 (October 2018): 80, https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/porcelain-made-lotus-shoes-qing-....

7 Edith C. Boynton Papers. Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections, South Hadley, MA.

8 Australian Museum, “Footbinding,” December 5, 2018, https://australian.museum/about/history/exhibitions/body-art/footbinding/.

9 Shepherd, Footbinding as Fashion, 3.

Give

Give