Global Migration Through A Photographer’s Lens

Engagement Intern Charlotte Smith ’24 reflects on her class visit to the Art Museum as part of Professor Serin Houston’s Fall 2022 geography course “Global Movements.” She describes close-looking activities in the Museum galleries and shares her newfound connections within the disciplines of art history and geography.

As an Art History major at Mount Holyoke, I’ve explored art from various geographical areas. However, prior to last semester I was not yet aware of the degree to which the study of art could intersect with the study of human geography. Being a student in Professor Serin Houston’s “Global Movements” class this fall was an exciting and eye-opening experience. Not only did I learn more about migration and thinking geographically, but I also found connections to the visual arts in ways I did not anticipate.

When I took the introductory course “World Regional Geography” in the fall of 2021, I felt my first sense of connection between geography and art history. After this course, I was drawn to explore the Geography department’s offerings and was thrilled to learn that my “Global Movements” class would include a session at the Art Museum to extend our learning outside the classroom. This also meant having the unique opportunity to blend my learning in the course with the work of my internship here at the Museum. As an Engagement Intern, I’ve been fortunate to experience class visits from a behind-the-scenes perspective, researching artworks and writing object summaries for classes visiting from diverse departments.

The first part of our “Global Movements” class visit to the Museum was a close-looking activity in the galleries led by Kendra Weisbin, Associate Curator of Engagement and Interpretation. My classmates and I each took a seat in front of two photographs by Lynsey Addario (American b. 1973), one depicting thousands of Syrian Kurds leaving Syria and crossing into Iraq, and the other, a woman and her five children in their tent at a squatters camp in Turkey.

Laura Shea - VIEW OBJECT DETAILS

Lynsey Addario (American, b. 1973), October 22, 2013. Iman Zenglo, 30, sat with her five children in their tent at a squatters camp outside of the Kilis refugee camp on the Turkish side of the border with Syria (#11 from the series Syria’s Refugees, 2013 capture; 2015 print

After discussing the images separately and learning more information about the photographer, we shifted the conversation to a comparison of the two works. Kendra set the stage by asking, “If you were a news editor, which photograph would would choose to represent Syrian migration?” With a show of hands, it was clear that the majority of the class leaned toward Addario’s photograph of Iman Zenglo and her family. “It just feels more personal,” one student said, “like we are learning about their individual circumstances and getting an intimate look at life in a camp or refugee shelter.”

However, as the comparisons progressed, another student pointed out the inherently artistic qualities of this image’s composition, like the dramatic lighting and positioning of each figure, suggesting a problematic romanticism or glorification of the refugee experience. With this insight, I noticed that the closeness and tenderness between the mother and child bore a resemblance to the Madonna and Child from Italian paintings of the 14th–16th centuries. This was further emphasized by magnificent beams of light surrounding them. We asked ourselves questions like “is this image religious?” and “what does it mean to see this western iconography in an image presenting the Syrian migration?”

Laura Shea - VIEW OBJECT DETAILS

Lynsey Addario (American, b. 1973), August 21, 2013. Thousands of Syrian Kurds flowed from Syria across the Peshkhabour border crossing into Iraq’s Dohuk Governorate (#3 from the series Syria’s Refugees), 2013 capture; 2015 print

While listening to everyone’s thoughts and perspectives, it was clear that there could not be a unanimous choice between the photographs. Each photograph enlightened our perspectives, yet led us to question the way migrants were represented. It made us think deeply about the ways each photograph would function in the context of mass media, as well as how we view these images ourselves. This connected us with one of the course’s main goals: to critically evaluate representations of migrants and migration in popular press. Reflecting upon our time in the Museum, Professor Houston shared that engaging with the physical works in the Museum is a great supplement to viewing digital images in the classroom or on a computer. This practice is “so important to our collective learning,” she says, and allows us to unpack the many “power dynamics and implications of different forms of representation and the ways we respond to them.”

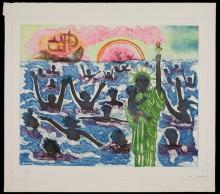

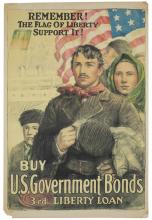

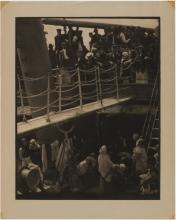

Following the class discussion, we all gathered in the Carson Teaching Gallery. We each chose a seat in front of one of five objects around the room, forming small groups of four students. The objects ranged from photographs and etchings to handmade leather sandals. As we looked at works by artists like Alfred Stiegliz, Faith Ringgold, and Hector Dionicio Mendoza, we shared our observations and interpretations of the piece in front of us. However, the groups were not given titles or descriptions of the works—we first had to observe.

My group studied Hector Dionicio Mendoza’s Immigrant Shoes, a sculpture made of handmade leather huarache sandal, metal ice-skating blades, rubber cement, and thread. Our initial confusion steadily transformed into a lively discussion about contrasts and opposites, noting the stark difference between the sharp metal blades and the smooth leather. We asked each other, “is this piece meant to be functional or metaphorical?”

With time, we determined that the juxtaposition of this piece is indeed metaphorical, an embodiment of the crossing between different climates and cultures. It was only then that Kendra shared additional information including a brief description of the artist’s intention and inspiration for the work. We learned that this artwork is also a symbol of immigrants such as the artist who have migrated from southern to northern regions, and were confronted with new temperatures and climates as well as new ways of life. Overall, the piece suggests the transitional space of migration and the joining of identities.

This small group session was an opportunity to actively observe additional visual representations of migrants and migration while working closely with classmates to draw conclusions about why the artist created the piece. Both the close looking experience and the small group exercise gave us a chance to see firsthand how migration is so often expressed to broader audiences through visual media. Spending time in the Art Museum helped us achieve Professor Houston’s goal of “engaging with different two-dimensional visual and three-dimensional sculptural representations of migration to deepen everyone's critical visual literacy and critical analysis skills.”

This class visit to the Museum was an exciting opportunity to blend my knowledge and practice in art historical observation with my exploration of geography. It was an exciting and enlightening experience that truly illustrated the plurality of how migration is approached and represented in many differing visual forms across time and place. This experience will inform my cross-disciplinary studies as I continue to explore the intersections between art history and geography for a long time to come!

I created a zine for my Creative Work assignment later in the semester, inspired by the images and discussions in our museum visit. It's available to view or download!

Give

Give