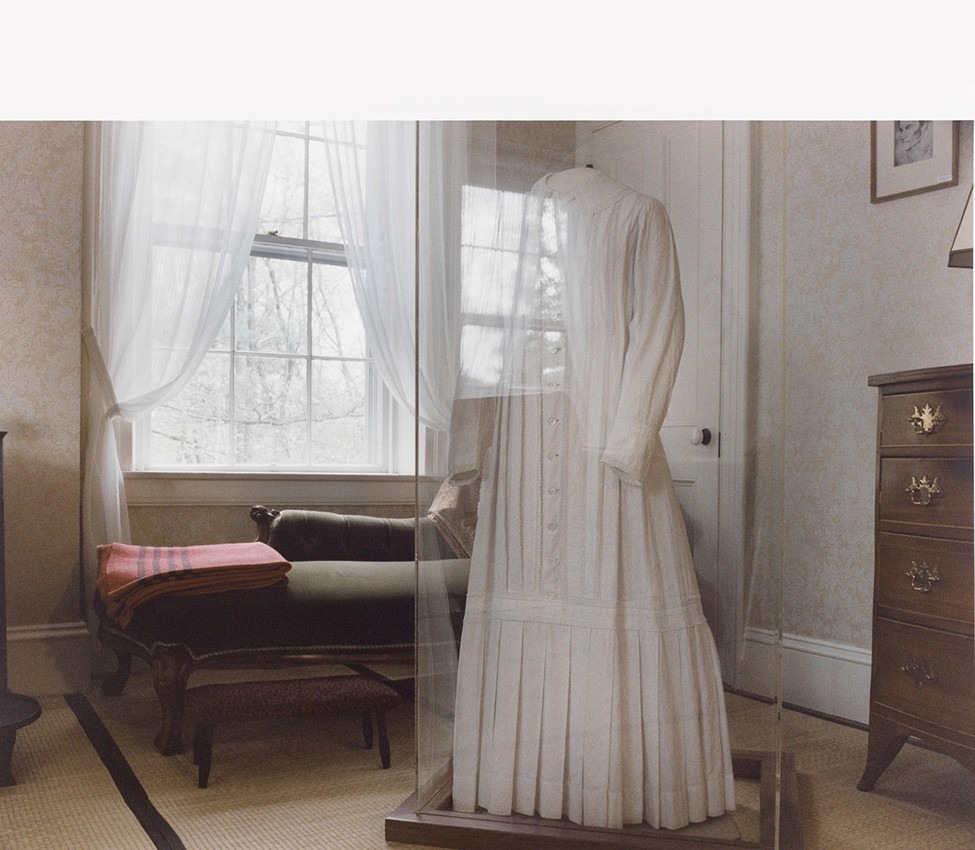

Emily Dickinson's White Dress, The Homestead, 1989

Mount Holyoke College President Lynn Pasquerella has provided the first post for the mhcameo column Objects of Our Affection, a series of personal reflections about works of art in the MHCAM collection. Here, President Pasquerella meditates over a photograph by Jerome Liebling (American, 1924-2011) of poet and Mount Holyoke alumna Emily Dickinson's ethereal white dress.

Objects of Our Affection: Emily Dickinson's White Dress, The Homestead, 1989

From the minute I entered the stunning Energies and Elegies exhibition at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, I was drawn to Jerome Liebling’s 1989 photograph Emily Dickinson's White Dress, The Homestead. Indeed, I confess to returning to the gallery on three consecutive days to further engage with the piece that I found so captivating. Liebling’s image of Dickinson’s white dress portrays both the bedroom window she peered through daily while living in Amherst and a reflection of a window in the garment’s plexiglass encasement. The dress, which stands as if inhabited by Dickinson’s ghostly presence, is mesmerizing.

As a philosopher, my mind immediately turned to the philosophical problem of “presence in absence,” or what the Scholastics termed “intentional inexistence.” Referred to by William James in The Meaning of Truth, the conundrum arises from the possibility of our beliefs and desires being directed upon objects that do not exist, leading some philosophers to maintain a distinction between mental phenomena and physical phenomena. And despite the emergence of sophisticated technology that can identify and map brain states in relation to people’s mental states, the debate over the reducibility of the psychical to the physical rages on. At the center of this controversy is whether there are minds or souls, in addition to bodies, that can exist independently from our bodies upon death.

Such metaphysical considerations are everywhere in Dickinson’s work, and while staring at Liebling’s photo, with the bare trees in the background and gray light casting images, I couldn’t help but recall one of Dickinson’s most famous poems regarding these questions: “There's a certain Slant of light” (320). She writes,

There's a certain Slant of light,

Winter Afternoons –

That oppresses, like the Heft

Of Cathedral Tunes –

Heavenly Hurt, it gives us –

We can find no scar,

But internal difference –

Where the Meanings, are –

None may teach it – Any –

'Tis the seal Despair –

An imperial affliction

Sent us of the Air –

When it comes, the Landscape listens –

Shadows – hold their breath –

When it goes, 'tis like the Distance

On the look of Death –

Whether life is rendered meaningless by the inevitability of death is a theme infused throughout this poem, and “the internal difference where meanings are” to which she refers, were a feature of Dickinson’s Mount Holyoke education.

Religious revivals were commonplace during the period of her studies at Mount Holyoke, which she began at the age of sixteen. Of the three groups into which students were categorized--those who professed, those who hoped to, and those who were without hope--Dickinson was famously among the thirty or so who remained without hope by the end of the 1847-1848 academic year. Her rejection of blind faith and the courage to risk the scorn of her teachers and peers in service to intellectual honesty was emblematic of the way in which Dickinson lived her life. The elusiveness of this level of character, then and now, is what is present via Dickinson’s absence in Liebling’s glorious chromogenic print.

-Lynn Pasquerella, President, Mount Holyoke College

Give

Give