Art on the Brain: A Conversation with Professor Sue Barry

This fall, Mount Holyoke Professor of Biological Sciences Sue Barry taught her groundbreaking course “Art, Music, and the Brain” in the Museum for the last time before her retirement from teaching. Her students—along with the entire MHCAM staff—will miss having an art-savvy neurobiologist in our midst.

Photo Credit: Rosalie Winard

Art on the Brain: A Conversation with Professor Sue Barry

Photo Credit: Rosalie Winard

Interview by Ellen Alvord, Weatherbie Curator of Education and Academic Programs

How did you come to teach a neurobiology course about art and music?

I first decided to teach this course because of the influence of my father and the way he taught me to see the world. For example, he once pointed to a circular clock located directly ahead and asked me if it looked circular. Then he told me to look at it from a different angle. Although it no longer looked circular, he reminded me that I would still draw it as a circle. “That's because you're drawing from what you know rather than what you see," he explained.

These different ways of looking at the world really intrigued me. I thought, "Okay, what is it about art and music that helps to shape our brains?" Sure, if you're an artist or a musician, your take on the world is going to be a little different than if you're not. But all of us are somewhat musical and artistic. Music is not just for Beethoven and art is not just for Picasso. All of us have some ability to make art or music, an ability that can improve over time. So what is it about our brains that drives us to make art and music? And what is it about art and music that then changes our brains?

When did you first start teaching this course at the Museum?

After I started teaching this class in the spring of 2005, I would have the students go to the Museum to evaluate a work of art and write about it. Laura Shea [MHCAM’s photographer] noticed these students coming in and looking at the paintings. Laura told Wendy Watson [the Museum’s curator at the time], who then wrote to me asking about my assignment and added “Why don't you just teach the class here?" In 2007, I started teaching the class in the Museum. So that’s how it all began.

How is it different to teach with original works of art and not just digital images?

It's important to see an actual painting as opposed to some digital display on a computer where you cannot see the thickness of the brushstrokes. The colors that you see on the computer screen are not necessarily the real colors, and the sizes of all the works appear similar since they will be the size of the computer screen or smaller. You are just missing so much of the experience of looking at a painting or a sculpture when you look at a digital reproduction.

Photo Credit:

Photo Credit: Ellen Alvord

Ellen Alvord

What inspired you to incorporate hands-on art activities into your class sessions at the Museum?

Doing all the different art activities really came from suggestions made by the staff at MHCAM. In particular, Brian Kiernan [the Museum’s preparator at the time], who was an artist and art teacher, had all sorts of interesting ideas for the activities. A lot of what I was teaching overlapped with concepts he understood as an artist. Although we used different vocabulary, we were basically talking about the same things.

How have these creative exercises impacted your students’ learning?

Many of the students in the class are science majors, and when we ask them to do a hands-on, creative exercise they are initially reluctant because they do not consider themselves to be artists. The last two times I have taught the class, my students have also learned how to play the violin, and they may not consider themselves to be musicians either. But I think the students really came to enjoy these exercises. Indeed, we often have a hard time pulling them away from the activity when the time is up. So, in addition to the hands-on activities illustrating all the points we are trying to make, I think the students discover that they can enjoy working with their hands. That, to me, is really satisfying.

Do you think the hands-on exercises stimulate creativity?

My dad was not only a professional artist but also a very good violinist, and as a result, he had a certain way of seeing the world that came through using his hands. I think that our intelligence, our sophisticated brain, emerged as we developed a greater ability to use our hands as well as more sophisticated motor and sensory systems.

Now that we are doing everything on the computer and we are not using our hands as much, I think that there is a certain type of intelligence, imagination, and creativity that could be reduced or lost. It's the kind of intelligence my father had, the way he saw the world, the way he could imagine things in his head, and draw, remember, manipulate and build things. So to me, the hands-on activities foster creativity.

Salma Jafiq '16, Erica Rayack '16, and Heidi Cheng '16 show off their luminance project with an Ansel Adams photograph.

Can you give us an example of one of the art exercises that enhances the scientific concepts you are teaching in this course?

Luminance is one of the most difficult concepts we cover, and the art exercise really makes it easier to understand. Artists use the word “value” – how light or dark something is – to talk about luminance, and, importantly, we use luminance to perceive space, depth, and form. For the activity, we ask the students to recreate black and white photographs from the Museum’s collection in non-representational colors by tearing and assembling bits of construction paper that match the shape and luminance of the parts of the photograph. They essentially make a color collage that resembles the photograph while staying true to the picture’s range of luminances or values. It always surprises me how well the collages come out, especially when we take grayscale images of the final works and see how much they look like the originals, at least from a little bit of a distance. I think it really helps the students understand how we perceive lightness, space, and depth.

In what ways do biology and art overlap with one another?

There are obvious things like, "How do we see and perceive and thereby create art?" but another thing that really intrigues me is this: you can show a two-year-old child a duck—a real duck—and the child will say, "duck." Then you can show him a rubber ducky, a bright yellow bath toy, and he'll say, "duck." Then you can show him a picture of a duck from a book and he'll say, "duck." How is it that the child sees all of these different representations–one being the actual duck, another being a simple 2D sketch made up of only a few lines, a third being a more cartoon-like rubber ducky,–and recognizes all of them as “duck”?

Do you know the answer to this?

I do not have the answer to this, but we would not be creating art unless we had this ability to take something that's out there, put it on a piece of paper, and look at it and say, "Yes, I know what you're representing."

Or, you take a photograph of something, let's say, of a building like the library, and it's now on a 3 x 5 card, and you look at it and you say, "Oh that's the library," even though it's only three by five inches. It is not the big building. How is it that we are able to make that leap? If we could not make that leap we would not be making art.

Did your personal experience with your vision and vision therapy change the way you teach?

I have been cross-eyed all my life, and even though it was not said bluntly, the message I got as a child was "You have a defect. You cannot control your eyes and you have to go to the hospital to get it corrected." After three different surgeries, when I still did not see better and was struggling in school, I was told, "Well, there's a problem with your brain which didn't wire itself up in a normal way so that you can coordinate your eyes, fuse images, and see in 3D. Moreover, scientific experiments indicate there is no way to change that. It's impossible for you to have normal vision."

Then, when I was 48 years old, I consulted a developmental optometrist and undertook vision therapy. I discovered that with proper training and lots of practice, I could indeed learn to coordinate my eyes. I could learn to fuse the images from the two eyes and see in 3D. No surgeon could correct my problem. It was up to me to fix a problem that had hounded me since childhood. This was one of the most empowering experiences of my life and also the most important lesson I have learned.

It affected my teaching because I now tell my students not to shortchange themselves, not to let somebody else tell them what it is that they cannot do, not to give up on something and assume it is impossible. With a lot of training and practice, you can accomplish things that you did not think were possible for you to accomplish. That is how vision therapy really affected my teaching. I do not ever want to be the kind of teacher who tells people, "Sorry, it's impossible. You'll never get there."

Photo Credit:

Photo Credit: Ellen Alvord

Ellen Alvord

The past two years you’ve taught this class with Professor of Music Linda Laderach. How did you come to co-teach this latest version of the course?

Early on, Linda actually sat in on the class, and she was fascinated by it. Then a couple of years ago, she asked me if she could co-teach it, and I thought that would be really fun. What I have discovered is that she is a fantastic teacher. And what she teaches in our class – how to play the violin – is very different than teaching, say, a biological concept. It is very hands-on. You have to teach the students new ways of doing things, and she is terrific at it. So it has been really fun to watch her teach, as well as to get more input on the material we teach together about music.

Do you have a favorite work of art at the Museum?

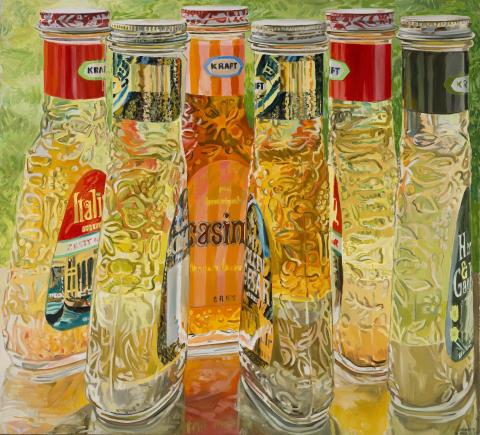

I love the salad dressing bottles by Janet Fish. They are so 3D. They feel like you could reach in and just pick them up. I love the way she is glorifying them. They are just salad dressing bottles, not even fancy salad dressing bottles. They are run-of-the-mill, supermarket salad dressing bottles, but they are beautiful... the way they reflect the light and everything. They are big! I just love that painting. I love all of her work.

The other piece of art that I will always love is the photograph by Ouyang Xingkai, the one with the elderly Chinese doctor. To me there is just something so human about it, the way the old man is taking the little girl’s pulse. That is what he is doing. He is sensing the beating of her heart. She's looking at him like, "What do you feel?" It gets to me every time, that photograph.

The Museum wishes to thank Sue Barry for her long-standing collaboration and support for our Teaching with Art program. We wish her well with the many projects she plans to pursue in her retirement.

Give

Give