Constructing Narratives from Vernacular Photographs

Constructing Narratives from Vernacular Photographs

I spent nearly every Friday afternoon of my final semester at Mount Holyoke with a collection of captivating everyday photographs, gifted to MHCAM by Ann Zelle ’65. Working as a curatorial intern, I helped catalogue the over 200 vernacular photographs that make up this collection. With the help of Associate Curator Hannah Blunt, I also curated a selection of these photographs, now on display as part of the exhibition 140 Unlimited.

For my final paper for Professor Kimberly J. Brown’s cross-listed Africana Studies and English course, The Visual Culture of Protest, I again drew upon this rich collection. Using a Black Studies framework, Professor Brown’s course explores social protests through visual culture. My final paper (and coincidentally the last paper of my undergraduate career) examined two photographs from the Zelle collection in great detail. The paper was titled: “Constructing Narratives from Vernacular Photographs: African American Men in Uniform.”

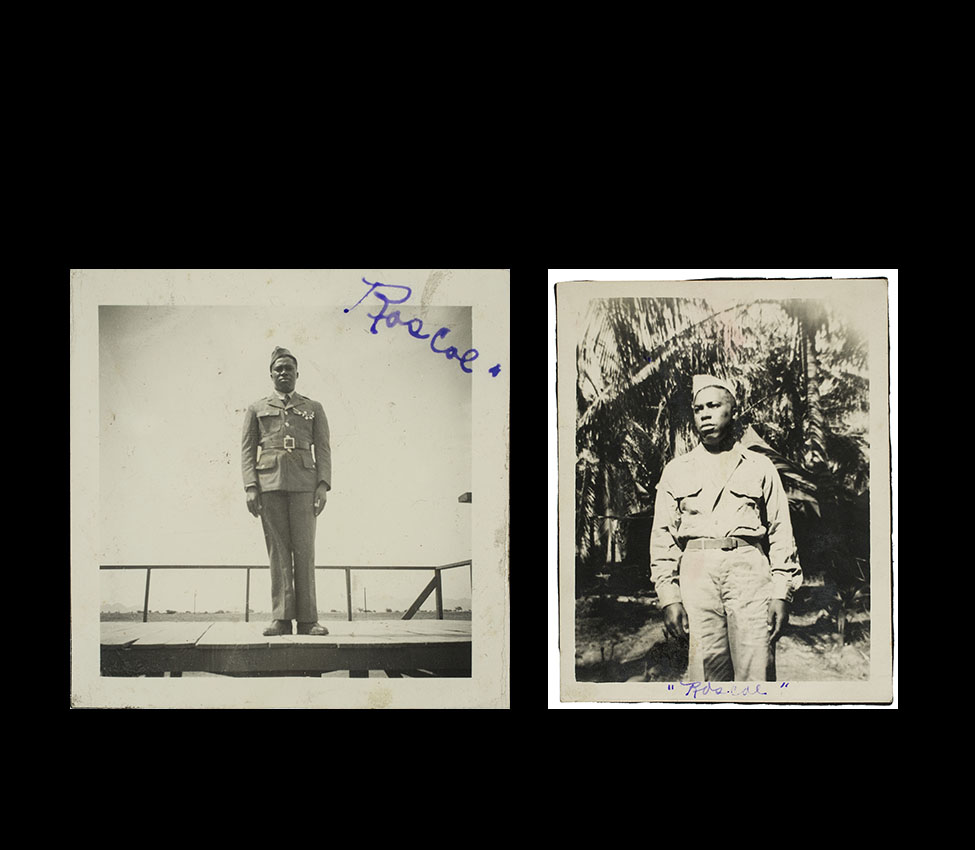

The two images that grabbed my attention were of the same man dressed in an army uniform. Vernacular photographs are often accompanied by little or no information leaving the images open to interpretation by each viewer. The only clear identifying features of the photographs are the man’s uniform and a name inscribed in purple ink: Roscoe. I was fascinated by this named, but unknown man.

Shot from a low angle, Roscoe stands at attention in his military uniform with the sky as a backdrop. Although taken outside of a photography studio, the image shares visual similarities to studio portraiture. Roscoe is formally dressed in his uniform and stands in an official-looking pose with his hands at his sides and feet together. He gazes back at the camera; at the photographer and the viewer. Vernacular photographs of African Americans such as this one of Rosco were often taken by other African Americans and challenged the racist and stereotypical images of blacks in America. They were a personal documentation of what it was like to be black in this country.

The formality of the first Roscoe photograph falls away in the second image. Here Roscoe is seen in a forested area. The angle is again from below, but Roscoe’s body is more relaxed and natural. He is no longer standing at attention and he is not returning the gaze of the camera. Although a larger photograph, this second image is less formal, more familiar and intimate. While studying these images I often wondered who took these photographs of Roscoe and for what purpose? Were they to be sent home to a loved one? Was it a black photographer who captured Roscoe’s image? And what compelled Roscoe to wear his uniform in these photographs? Did he enlist or was he drafted? What was his relationship to that uniform and all it represents?

The mysteries behind the photographs compel us to study them. They compel us to try and decipher meaning and identities. The beauty and power of vernacular photographs is that the truth may never be discovered. Those depicted will remain nameless. They could be anyone. With Roscoe, we know his name. We know his identity as a black American man who was also a soldier in the 1940s. We know he likely faced racial discrimination during his time in military service. That is all we know. But those that study Roscoe’s photographs will always construct narratives, and each person that views them will leave with a different reading of his image and his identity.

-Emma Kennedy ’16

GIVE

GIVE